Enrico Bossan è direttore di Colors e responsabile dell’area Editorial di Fabrica, centro di ricerca sulla comunicazione di Benetton Group.

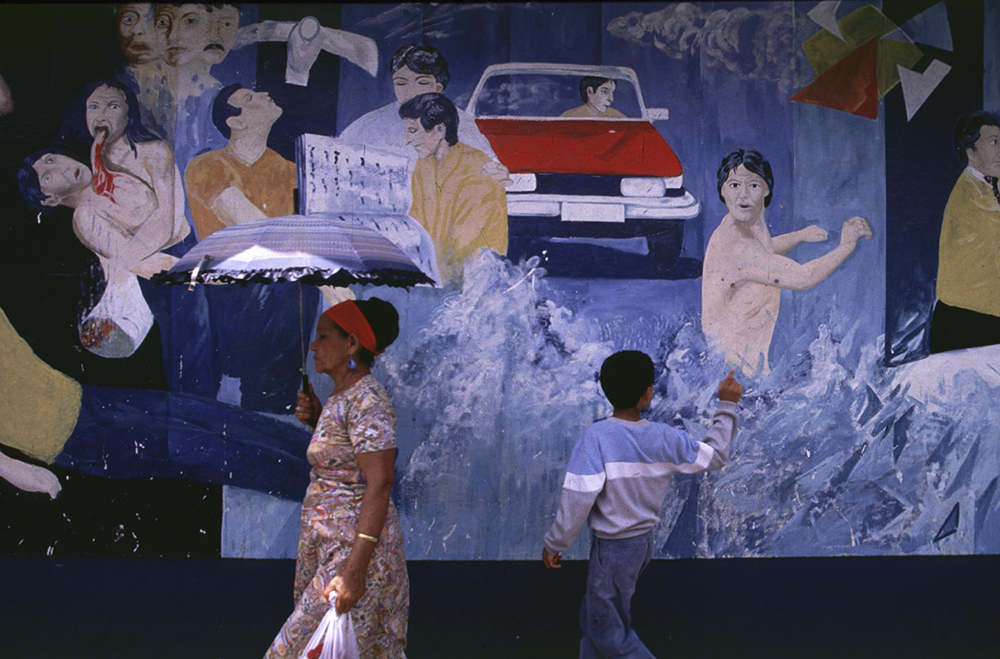

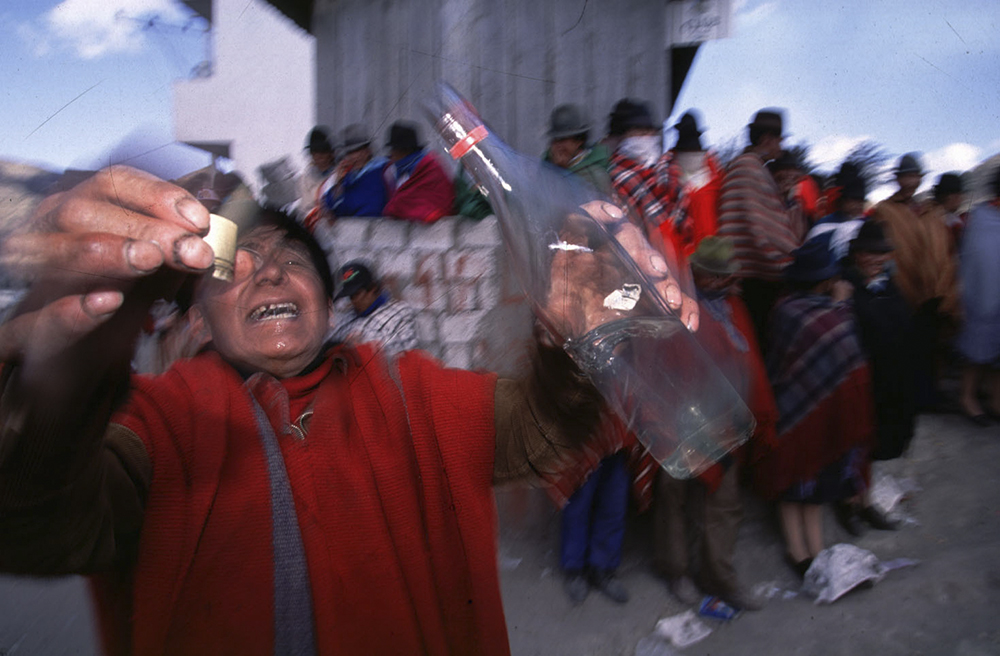

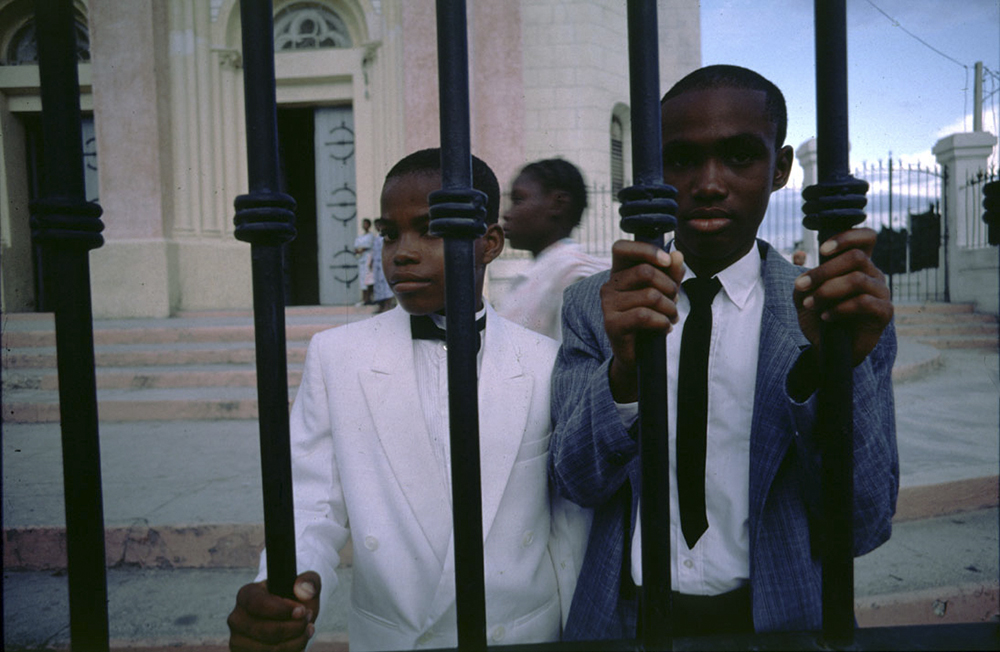

Fotografo professionista dal 1985, è docente, curatore di mostre e di progetti editoriali, spesso legati alla cooperazione e a progetti di solidarietà. Ha attraversato tutti i continenti, realizzando progetti a lungo termine come Latino, (nella gallery) costruito tra il 1986 e il 1992 nell'arco di frequenti ritorni in Sudamerica.

Con le sue immagini, pubblicazioni e progetti ha ricevuto numerosi premi e riconoscimenti in tutto il mondo.

A Phom ha raccontato le sue idee sulla fotografia e sul ruolo che essa ha oggi - o dovrebbe avere.

Crediamo che il tuo impegno professionale rappresenti un caso interessante di intreccio di competenze, ruoli e modus operandi. Sei al contempo in Colors, fotografo, responsabile di un masterclass e docente. Da dove nasce e come si è sviluppato questo approccio al lavoro?

Secondo la mia visione della fotografia il soggetto, chi fa la foto, è altrettanto importante dell’oggetto, chi è fotografato. Da questo deriva il grande interesse che ho sempre avuto per la fotografia a sfondo sociale: l’ottica non è mai stata di dimostrare se io potessi essere bravo o meno, ma invece di rendermi utile come potevo, per aiutare alcune ONG a comunicare - come ho fatto ad esempio con i Medici con l’Africa CUAMM di Padova, con cui collaboro da molti anni. Lavorare a Fabrica e Colors è stato, fin da quando ho iniziato nel 2005, un ulteriore sviluppo alle mie conoscenze e competenze, non inerenti solo alla fotografia, ma alla comunicazione in termini più generali. Grazie a questo incredibile luogo ho potuto incontrare personalità interessanti e lavorare a progetti unici.

Lavorare in Colors ti consente di alimentare continuamente uno sguardo internazionale su aspetti molto connessi tra loro, come la comunicazione, la creatività e la fotografia. Com'è, vista dal tuo osservatorio privilegiato, l’evoluzione della fotografia?

Da questo punto privilegiato la fotografia continua ad essere una centralità nella comunicazione e nel mostrare i cambiamenti sociali, culturali, politici e non per ultimi artistici dei nostri tempi.

Quanto conta la dimensione tecnologica, oggi, nella produzione e diffusione della fotografia e quale relazione si instaura con la dimensione dell’espressività e della creatività?

La fotografia è tecnologia: è un’invenzione tecnologica e per questo nella sua breve ma intensa storia ha più volte ridefinito lo strumento con cui le immagini vengono realizzate. Dai dagherrotipi al digitale, l’immagine ha vissuto diverse fasi, senza che una abbia prevalso sull’altra. E’ stato un continuo svolgersi e reinventarsi alla ricerca dello strumento più idoneo per raccontare mediante immagini. Oggi la fotografia digitale (prodotta da qualsiasi tipo di device) come mai prima ha avvicinato tutti a prendere delle foto.

Ritieni che ci siano elementi culturali, economici e sociali che consentono più di altri di sostenere l’evoluzione di un sistema fotografia? e se si, esistono paesi, aree geografiche dove questo accade in modo più marcato che in altre?

Inevitabilmente esistono Paesi con maggiori opportunità di accesso alla tecnologia e alla forme di divulgazione della cultura (es. spazi museali). In queste realtà è logicamente più facile entrare in contatto con il passato e con le nuove generazioni. Questo non significa però un paese con poche risorse non possa avere delle eccellenze. La semplicità della fotografia consente anche alle realtà più semplici di emergere.

Come vedi la situazione nel paese Italia?

In Italia la fotografia vive un momento di grande vivacità, ma al contempo di grande contraddizione dal punto di vista commerciale, poiché mancano risorse che in passato il mondo dell’editoria e della pubblicità mettevano a disposizione.

Nel tuo ultimo progetto "Iranian Living Room"si concretizzano due cose che ci sembrano particolarmente interessanti:

- il progetto è realizzato da un collettivo di giovani fotografi iraniani,

- viene costruita un’altra rappresentazione di cos’è l’Iran, attraverso uno sguardo più privato, rivolto a quei luoghi e situazioni meno conosciute. Puoi parlarcene?

Fabrica accoglie giovani di talento da tutto il mondo e offre loro una possibilità di crescita professionale e umana unica. Con questo progetto l’idea è stata di dare un’opportunità a giovani con altrettanto talento, che non stavano a Fabrica. Ne è uscito un ritratto inedito dell’Iran: con occhi discreti e incondizionati essi hanno raccontato il salotto di casa iraniano, spazio fisico e metaforico nascosto agli sguardi dei media internazionali e dello stato locale.

In un sistema ideologico che ha imposto un proprio modus vivendi, il soggiorno di casa assume così funzioni di utilizzo differenti – salone di bellezza, luogo di culto, spazio per la festa o dove organizzare cerimonie - costringendo la società a trasferire nell’ambito privato ciò che non può essere vissuto in pubblico. Gli scatti dei giovanissimi fotografi raccontano stanze segrete e inaccessibili ai giudizi degli altri dove effettivamente si svolge la vita.

Questo progetto è stato pubblicato da Fabrica. In una recente intervista radiofonica dici che nel dna di Fabrica c’è l’intenzione di dare voce a chi non ce l’ha. Cosa significa operativamente per una realtà legata ad un’importante brand commerciale operare in questo senso? e la fotografia aiuta a sviluppare questa intenzione?

Dare voce a chi non ce l’ha è una cosa che mi ha sempre interessato, e a Fabrica ho trovato un interlocutore più alto su questo tema. Mi è sembrato vitale su un tema così complicato ascoltare gli artefici del cambiamento che l’Iran sta vivendo. Fabrica non è un brand commerciale. Benetton crede nello sviluppo delle idee e nei giovani e Fabrica è l’espressione della filosofia di Benetton nella comunicazione.

Rispetto alla tua produzione fotografica ritroviamo un aspetto che ci sembra costante del tuo approccio. La necessità di andare oltre le rappresentazioni stereotipate e di costruire uno sguardo più aderente alle varie dimensioni della realtà. Come in “èAfrica”. È così?

Lo stereotipo deve sempre spaventarci e suscitarci diffidenza. Il lavoro di tutti noi deve essere di combattere lo stereotipo, i luoghi comuni. Il mio è semplicemente un tentativo di cercare un altro punto di vista. Non è detto che ci riesca sempre, ma è importante provarci.

Cosa ti permette di andare oltre, “trasformare la retorica e i pregiudizi in storie di vita”? Riguarda i contenuti e/o l’uso di un linguaggio fotografico? Ci piacerebbe approfondire questo aspetto.

Io non ho la presunzione di raccontare storie di vita, quello che faccio è immergermi in queste storie. Se poi talvolta riesco a restituirne alcune parti, allora sono soddisfatto del mio lavoro. Per fare questo è importante non solo l’uso di un linguaggio fotografico, si tratta prima di tutto di una presa di posizione, di un impegno sul campo.

In molti tuoi lavori “Benares”, “Mozambico”, ma anche in “Health” le fotografie ci portano in mezzo allo scorrere quotidiano della vita delle persone in quei luoghi. Non c’è enfasi, e lo sguardo sembra sempre rispettoso pur calandosi in una stretta relazione con le persone. Anche quando la fotografia appare cruda sembra appartenere a questo scorrere della vita. È una caratteristica che ricerchi nei tuoi lavori o fa parte di situazioni particolari?

Non credo che sia parte di me cercare lo scoop e l’immagine d’effetto. Ho sempre pensato che la vita di tutti i giorni possa essere più interessante perché meno eclatante, più privata, nascosta, intima, si deve ritagliare dalle pieghe di momenti che tutti noi viviamo. Sono questi momenti che generano spesso i grandi mutamenti.

Hai lavorato molto in Africa, e, ad esempio, in “Danza Uganda” e “Neramadre - Pediatria” il rapporto con le persone fotografate è molto intimo. Come ti accosti alle persone, ai gruppi che fotografi che appartengono a culture diverse dalla nostra.

Le mie prime immagini erano delle immagini di paesaggio urbano. Notavo però che riguardandole non mi suscitavano nessun interesse. Mi dedicavo a un esercizio di mera estetica fine a se stessa. Solo ascoltando il mio corpo e la mia relazione con lo stare in mezzo alle persone, anche con la macchina fotografica, ho potuto vedere il mondo che mi circondava in modo meno superficiale e più empatico. Se volessi tradurlo in un esempio molto semplice, è come quando in alcuni momenti sentiamo dei brividi che scorrono lungo il corpo. Posso riconoscere il momento in cui ho sentito questi brividi per la prima volta: nel giugno del 1981, quando, abbondanando il tema del paesaggio urbano, decisi di confondermi in una spiaggia in mezzo alle persone. Improvvisamente lì, in quella circostanza, ho smesso di sentirmi inutile.

Quando fotografi a colori li usi saturi e vivi. In particolare in “Exit” come anche in “Latino”. Hanno una funzione specifica nel tuo linguaggio visivo? e quando passi al bianco e nero cosa cambia?

Ho sempre pensato che la fotografia a colori avesse una relazione con la mia data di nascita (1956). Sono nato nell’era in cui il colore ha rappresentato un cambiamento sociale rilevante nella vita di tutti i giorni, dalla segnaletica, all’architettura, agli oggetti della vita quotidiana. Un desiderio che vorrei definire una fame di colore che non mi ha mai fatto pensare che fosse una scelta non appropriata. Probabilmente le mie radici materne, affondate nel Sud, mi riportavano ai colori saturi, ricchi di sapori e di densità e mi è venuto naturale voler rivedere le mie immagini con questo tipo di tono.

A noi pare anche nella tua produzione fotografica ci sia una continuità narrativa che la caratterizza. Tra i diversi reportage scorra un necessità di raccontare il mondo volendo far emergere alcuni aspetti piuttosto che altri. È cosi?

Ho sempre cercato di avere un perché che fosse legato alla mia identità. In una prima fase mi sono cercato come persona, come essere, probabilmente girando anche un po’ a vuoto e senza senso, ma questo cercarmi mi ha permesso di capire l’importanza di trovare un punto di partenza e un punto di arrivo per ogni mio progetto. Un esempio per tutti: quando per sette anni ho percorso l’America Latina è stato perché i racconti di un amico migrato in Venezuela da ragazzo mi hanno fatto sentire quel continente quasi l’estensione del mio Paese di origine; ho trovato nelle sue parole dei suoni, dei ricordi, dei colori che mi esortavano ad andare. “Latino”, il nome con cui ho chiamato questo progetto, è il viaggio che ti riporta al luogo da cui sei partito.

Nel tuo lavoro di fotografo pensi a quale posizione avremo noi come spettatori delle tue fotografie? cosa pensi che faremo di fronte ad esse?

Non mi aspetto nulla dai rimiranti e non mi sono mai nemmeno immaginato che cosa potrebbe fare il pubblico davanti alle mie immagini. Sarebbe più importante per me sapere come le mie immagini eventualmente possono coinvolgervi e la ragione per cui lo fanno.

Cosa ne pensi delle produzioni multimediali e dell’intreccio tra video e fotografia? (hai anche diretto anche un cortometraggio)

La fotografia è guardare un singolo frame. Credo che la forza del frame sia il senso della fotografia.

Nel rapporto con le nuove tecnologie digitali (sia smartphone che app specifiche come Instagram) si intravedono sia problemi di varia natura, legati, ad esempio, alla precostituzione delle forme estetiche, sia occasioni per continuare nell’evoluzione del linguaggio fotografico. Cosa ne pensi?

Tutto può partecipare all’evoluzione della fotografia, non solo l’aggiornamento tecnologico dei device, ma anche tutte le applicazioni ad essi collegate. Credo inoltre che tutti i social network possano partecipare allo sviluppo e alla divulgazione dei contenuti. Il tutto si mescola in un caleidoscopio che può portarci a rileggere le forme estetiche ma anche allo stesso tempo ingannarci nell’effimero.

A chi passi il testimone?

Ad Anthony Suau.

Intervista a cura di Marco Benna

ENGLISH VERSION

Enrico Bossan is the director of Colors magazine, and the editorial manager of Fabrica, Benetton Group's Communication Research Centre.

A professional photoreporter since 1985, he is also a teacher, a curator and an editorial project manager. He's often been involved involved in cooperation and solidarity projects. He has travelled across all continents, working on long-term projects such as Latino, (see the gallery) that he released between 1986 and1992 during several trips to South America.

His images, publications and projects have received a number of prizes and acknoledgements worldwide.

He told us his ideas about the role photography plays nowadays - or should play.

We believe your commitment to photography represents a stimulating intersection between competences, roles and modus operandi. For Colors, you simultaneously serve as photographer, masterclass manager and teacher. How did this work ethic originate?

According to my outlook on photography, the subject who takes the photo is just as important as the object that is being photographed. This is where my interest in social-oriented photography originates. I’ve never been focused on proving how good I could be. Rather, I’ve always been eager to make myself as useful as possible and help specific NGOs communicate - like I’ve been doing for years collaborating with Medici con l’Africa CUAMM in Padua. Working at Fabrica and Colors since I started in 2005 has resulted in to a further development of my knowledge and competences - not only in terms of photography, but also in reference to communication in general. Thanks to this incredible space I’ve had the chance to meet extraordinary personalities and work on unique projects.

Working at Colors allows you to constantly nourish the international audience with interconnected aspects such as communication, creativity and photography. What’s the outlook you’re carrying out from your standpoint?

By this privileged perspective, photography keeps playing a central role within communication, in showing social, cultural and political changes - not nowadays’ artistic aims.

How important is the technological dimension in today’s production and diffusion of photography? What kind of relationship originates from expressivity and creativity?

Photography is technology. Photography itself is a technological invention, hence during its brief yet intense history it’s come to redefine the tool through which photos are taken - manifold times. From daguerreotypes to digital, the image has undergone several phases that haven’t overrun one another. It’s been a constant developing and reinventing the research of the most apt instrument to narrate through images. Today digital photography (carried out through any type of devices) has allowed for all crowds to approach photography.

Do you believe there are cultural, economic and social elements that allow for the evolution of a photography system more than others? If so, are there specific countries or geographical areas where this phenomenon is more evident?

It’s inevitable that certain countries provide more opportunities to access technologies and forms of cultural diffusion (see museum spaces) than others. In these circumstances it’s logically easier to keep in touch with both the past and new generations. However, that is not to say that a country with poorer resources will automatically lack excellences. Indeed the simplicity of photography allows even smaller realities to emerge.

What’s the situation like in Italy, according to you?

Photography in Italy is witnessing a period of bold vivacity. At the same time, it’s facing a commercial contradiction, because there’s a lack of resources that the publishing and advertising world would provide for in the past.

In your latest project "Iranian Living Room" we point out two fundamental characteristics: a) the project is realised by a collective of young Iranian photographers; b) it depicts Iran under a different light, through a more intimate insight (mostly focusing on less renowned places and situations). Could you tell us about it?

Fabrica welcomes young talents from all over the world and it offers them a unique chance of professional and personal growth. The idea behind this project was to give a chance to equally talented youngsters outside of Fabrica, too. It resulted into a never-before-seen portrayal of Iran. Through discreet and unconditioned eyes, they narrated the living room of the typical Iranian household - both a physical and metaphorical space that’s hidden from the international and national public opinion.

In an ideological system that has imposed its own modus vivendi the living room becomes a multifunctional space - beauty salon, worship area, recreational and ceremonial space. Thus it forces society to transfer all the situations that can’t be exposed publicly to the private sphere. The photos by the young photographers capture rooms that are kept secret and inaccessible to the judgment of others - rooms where real life is actually lived.

This project was published by Fabrica. On a recent radio interview you stated that the intent to give a voice to those who don’t have one lies within Fabrica’s DNA. Operatively speaking, what are the implications of this statement for such a commercial-oriented brand as Colors? And does photography help develop this intent?

I’ve always been interested in giving a voice to those who don’t have one, and at Fabrica I found the highest interlocutor in this regard. Considering the complexity of the subject matter, I deemed it vital to listen to the change-makers of current Iran. Fabrica is not a commercial brand. Benetton believes in the development of ideas and in youngsters - and Fabrica is the expression of Benetton’s philosophy in relation to communication.

We’ve noticed a common denominator to your photographic work and approach - that is the need to go beyond stereotypical representations, in order to build a vision that’s more adherent to the various dimensions that forge reality. We’re specifically thinking of “èAfrica”. Is that so?

We should always fear and distrust stereotypes. Our job must be fighting against stereotypes and clichés. As for me, I’m simply trying to provide a different point of view - which doesn’t imply I’ll always succeed at it. Still, keeping trying is of paramount importance.

What is it that allows you to go further and “transform rhetoric and prejudices into life stories”? Does it have to do with the contents and/or the use of a photographic language? We’d like to deepen this aspect.

I don’t really make the assumption I’m telling life stories - what I do is dive into these stories. Should I be able to give back something occasionally, then I’ll be satisfied with my work. In order to do so, using a given photographic language isn’t the only element at stake. First you have to choose a point of view and a specific commitment to the sphere of action.

In a number of your works (see “Benares”, “Mozambico”, and “Health”) photographs catapulte us right in to the daily flow of life of the people inhabiting those places. There’s no emphasis and it always feels as though your look is a respectful one - despite the fact that it creates a tight bond with the people you shoot. Even when photography may appear crude at first glance, it still seems to be partaking of this natural flow of life. Is it a specific factor you seek in your works or is it ascribed to particular situations?

I don’t think looking for a scoop and an impressive image is really me. I’ve always thought that everyday life can be much more interesting because it’s less glaring, more private and intimate. It has to be carved out of the folds of moments we all endure. It’s these little moments that often create big changes.

You’ve worked in Africa a lot. For instance, in “Danza Uganda” and “Neramadre - Pediatria” there’s a particularly intimate relationship with the people you portray. What’s your approach when you photograph people and groups who belong to different cultures than ours?

My first photos were urban landscapes. However, when I’d look at them I noticed they raised no interest in me. They were a mere aesthetic exercise for their own sake. It was only by listening to my body and my relationship with people (through the camera, too) that I perceived the world around me in a less superficial and more empathic way. To put it in easy terms, it’s like sensing shivers up your spine, spreading through your entire body. I can clearly detect the first time I had this feeling: in June 1981 I was parting from the urban landscape theme and I resolved to losing myself amongst people on a beach. Suddenly, right there and then I stopped feeling useless.

When you photograph in colour you use saturated and vivid colours - see “Exit” and “Latino”. Do colours play a specific role in your visual language? What changes when you shift to black & white?

I’ve always thought that colour photography had a special connection with the year I was born (1956). It was an era featured by the drastic social change brought about by the use of colour in everyday life, ranging from street-signs to architecture to objects of daily use. It’s a desire I’d describe as “hunger for colour”, and I’ve never thought it was the wrong choice. Probably my mother’s roots from Southern Italy would lead me back to saturated colours, as rich in flair and density as they are - so it was a natural move for me to review my photos with this type of colour.

We think that your photography is featured by a narrative continuity. Amongst your reports we notice a steady urge to tell about the world by focusing on certain aspects over others. Is it so?

I’ve always searched for a reason that is linked to my identity. First I tried to look for myself as an individual and a human being - possibly by roaming pointlessly, too. However, this quest to find myself has allowed me to learn the importance of fixing a starting point and a finish point for all my projects. Here’s an example: once I travelled through Latin America for seven years. A friend of mine had migrated to Venezuela and his descriptions made me perceive the whole continent as an extension of my own home-country. In his words I found sounds, memories and colours that incited me to go there. “Latino” (the name I gave to this project) is the journey that brings you back to the point where you started off.

In your work as photographer do you think of what position we’ll assume as spectators of your photos? How do you think we’ll react before them?

I don’t expect anything from the viewer and I’ve never wondered how the audience would react to my photos. It’d feel more important to me to know that my images may involve you, and why.

What’s your opinion on multimedia productions and the mishmash between video and photography? (You’ve also shot a short film).

Photography is about looking to a single frame. I believe the strength of the individual frame is the true meaning of photography.

The relationship with new digital technologies (both smartphones and specific apps such as Instagram) is both burdened by various problems - such as the pre-determination of aesthetic forms - and characterised by new opportunities to foster the photographic language. What do you think about that?

Anything may concur in the evolution of photography - not only the technological update of devices, but that of their linked applications, too. I also believe that all social networks can participate in the development and divulgation of contents. All this gets merged together in a kaleidoscope that may lead us to review the forms of aesthetics - but it may trick us into the ephemeral, as well.

The articles here have been translated for free by a native Italian speaker who loves photography and languages. If you come across an unusual expression, or a small error, we ask you to read the passion behind our words and forgive our occasional mistakes. We prefer to risk less than perfect English than limit our blog to Italian readers only .

Who are you going to pass the baton on and why?

To Anthony Suau.

We are a self-funded intiative, and we rely on the expertise each of us has gained in his/her field of specialty. Whilst presenting our interviews and articles, we are looking forward to your feedback to help us improve our English version - anything related to specific words, phrases or idiomatic expression, or any other annotation you might deem useful.

Please email us at info@phom.it.

Leave a Reply