Dal sito di Giovanni Marrozzini: "Giovanni nasce a Fermo nel 1971, la prima volta. Rinasce a Malta nel 2001 per merito dell’amico Andrea, che gli regala una poesia. Infine nasce in Zambia, dopo un attacco di malaria cerebrale, nel 2003. All’inizio fotografa per caso; da dilettante fotografa per professione. Da professionista fotografa per passione e per necessità espressiva. Aiuta le storie che incontra a evadere dai labirinti, assecondando le loro richieste. In Argentina conosce la Fata Turchina, in Camerun incontra Mosé. Vive in camper per un anno, senza dar segni rilevanti di instabilità mentale (o almeno così gli pare). È caparbio, istintuale, entusiasta. E possiede tre tesori: Mary, Leone e Francesco, in rigoroso ma provvisorio ordine di altezza. Ulisse, l’amato cane, se ne è andato per sempre quando il suo padrone è tornato da ITAca."

La narrazione è da sempre un elemento molto forte della tua fotografia, fino a mettere insieme delle storie composte da due o tre foto per costruire una geografia dell’Italia di oggi nel lavoro Itaca Storie d’Italia. Vuoi dirci cosa significa per te saper raccontare?

Estrarre un'esperienza dal flusso del tempo cercando nelle immagini che compongono la storia un legame simbolico che sia al contempo racconto e senso del racconto.

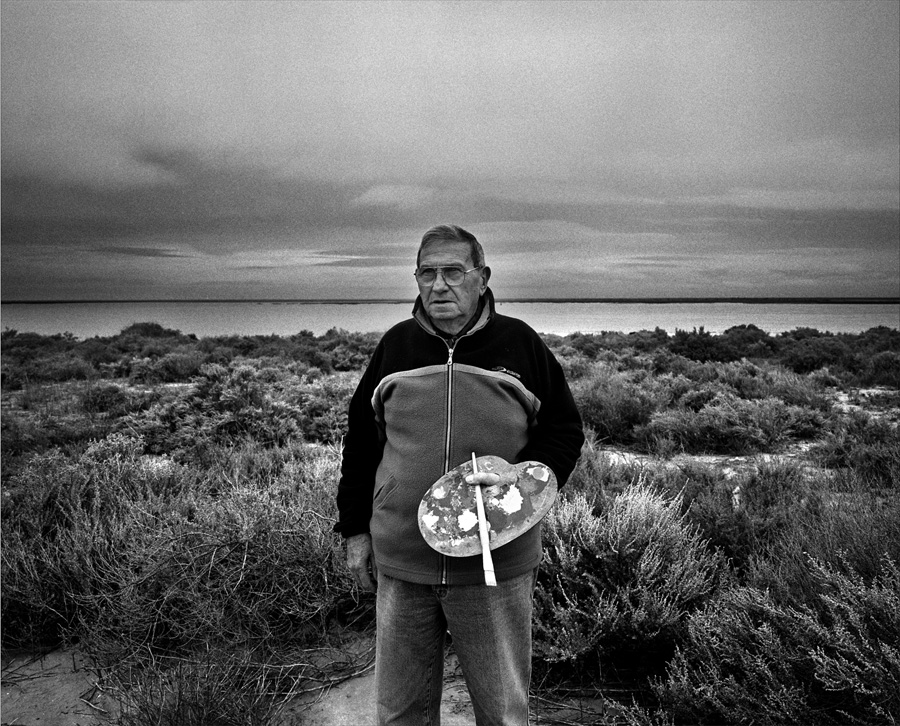

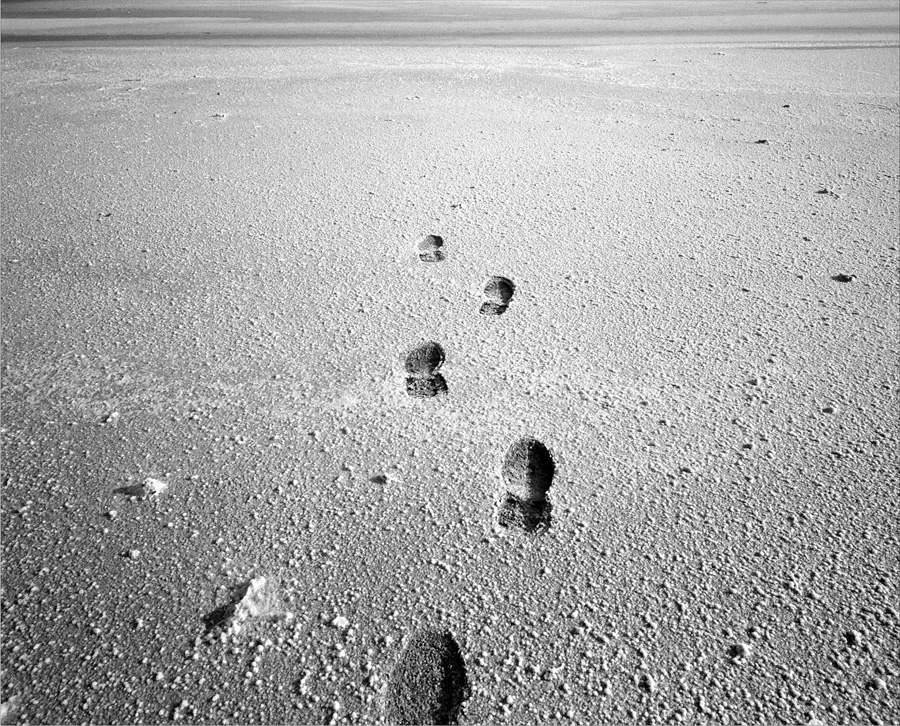

Non v’è tua immagine ove non vi sia un elemento umano, presente con il corpo o con i segni del suo passaggio: perché continuare a raccontare l’Uomo con la fotografia?

Perché no?

Alcuni video realizzati durante il viaggio di Itaca sono raccolti nel canale YouTube di Itaca Storie d’Italia: hai realizzato o hai mai pensato di sviluppare un tuo progetto usando i multimedia? Come vedi l'integrazione di fotografia e multimedia?

Laddove manchi il tempo perché un racconto decanti in profondità credo che l'integrazione tra fotografia e multimedia sia efficace perché risponde all'esigenza imperante di velocità nella fruzione. Il multimedia facilita la nostra capacità di assorbire una storia in pochissimo tempo, a scapito,forse, di una maggiore incisività della riflessione.

In Falene hai raccontato per immagini la vita in un istituto per ciechi e ipovedenti gravi in Etiopia, credo instaurando un rapporto diverso tra “osservatore” e “osservato”, solitamente fatto di reciprocità degli sguardi: come ti sei relazionato con loro? Questa condizione ha influenzato il tuo modo fotografare?

Al primo contatto restai sorpreso nel vedere come tutto funzionasse secondo una logica che solo adesso mi è chiara, come se le persone fossero mosse da fili invisibili, creando una sorta di giostra. I loro movimenti erano aggraziati e coreografici. Li ho guardati: le mani leggermente distanziate dal corpo, il passo accorto e mai veloce. Parlavano sottovoce, erano affettuosi, percepivano la mia presenza accompagnando la sorpresa con piccoli movimenti della testa e delle mani. Stavano captando segnali, odori, informazioni...poi, dopo qualche minuto di esitazione, esplodevano in un sorriso d'intesa e accettazione. Più di una volta si sono avvicinati alla macchina fotografica: solo dopo aver capito che era niente più di un pezzo di ferro, si slanciavano su di me toccandomi e abbracciandomi. Non posso sapere quale immagine della mia persona si sia materializzata nella loro mente. Mentre mi toccavano si sussurravano parole come volessero tutti assieme costruire la mia figura. Forse loro sono andati più a fondo di quanto sia riuscito a fare io.

Scatti sia in pellicola che in digitale, con due approcci forse leggermente diversi: ce ne vuoi parlare?

L'utilizzo della pellicola rende l'intera esperienza più "preziosa", in quanto si avverte il lavoro del tempo e il senso del limite. Ad uno scatto ne segue un altro, fino al termine del rullino, e alla fine della giornata, dopo aver etichettato tutti i rulli, si ha il tempo di metabolizzare l'esperienza della visione. Entrano in azione fantasia, desiderio e memoria, e una componente di pazienza: la camera oscura, infine, emetterà il suo verdetto, a volte sorprendente.

Hai realizzato diversi reportage nei quali hai instaurato un rapporto intimo con le persone. Come stabilisci questo rapporto con le persone durante il tuo lavoro?

Raccontare una persona è un'impresa le cui difficoltà maggiori risiedono nella capacità di entrambi di rendersi permeabili.

Nella tua comunicazione, per esempio su Facebook, si evidenzia un approccio al tuo lavoro dove il viaggio è centrale. Sia perché organizzi viaggi e li vivi, ci sembra profondamente, sia perché li descrivi dettagliatamente (cartine con i percorsi, fotografia del backstage, del veicolo, etc). Che relazione ha con la tua fotografia questa dimensione di viaggiatore?

Mi invito da solo ad un viaggio che mi somiglia tanto e sottilineo sempre e solo quello che attraverso il viaggio scopro di non sapere di me. Questa è la risposta poetica. Prosaicamente dico che un fotografo è costretto a viaggiare perché la maggior parte delle committenze gli impongono di farlo.

Sappiamo che stai preparando un lungo viaggio in cui attraverserai il continente africano dall’Egitto a Città del Capo: vuoi darci qualche anticipazione sul progetto?

È un progetto molto ambizioso su cui sto lavorando da circa 6 mesi. Scaramanticamente preferirei non parlarne...almeno per ora.

La preparazione di un tuo reportage o lavoro fotografico come avviene?

a) Approfondisco la tematica che andrò a trattare

b) Definisco preventivamente i tempi realizzativi

c) Scelgo la macchina fotografica idonea per il servizio

d) Prendo contatti con persone del luogo che poi, solitamente, saranno le mie guide.

e) Mi faccio pagare un acconto

f) Spesso non mi pagano l'acconto e non parto più

g) Mi incazzo

Il tuo recente lavoro fotografico Itaca (qui il video dell'inaugurazione della mostra) dimostra un particolare eclettismo fotografico. Intendiamo una capacità di fotografare attingendo alla molteplicità del linguaggio fotografico. La tua formazione visiva ed estetica dove nasce e come si sviluppa?

Non ho mai frequentato una scuola di fotografia, quindi posso dire che nasce il 12 settembre del 1971 e si sviluppa in 42 anni.

Un aspetto del tuo lavoro fotografico che ci incuriosisce è la densità dello sguardo, un lavoro molto ricco di sfumature. Cosa fai con la fotografia e cosa fa a te la fotografia?

Non lo so. Fai delle domande difficili. Cosa faccio con la fotografia? Mi racconto delle storie. Cosa fa a me la fotografia? Mi ascolta.

Sappiamo anche di un tuo interesse verso i rapporti tra letteratura e fotografia. Ne vuoi parlare?

Tutti gli scrittori sono turbati dalla fotografia, e tutti i fotografi, di solito, subiscono il fascino della letteratura. Baudelaire, tra gli altri, bocciava la fotografia descrivendola come uno strumento incapace di soggettività e inadeguato, per non dire contrario, al mondo espressivo dell’arte. Ma se la sovranità sui cinque sensi e sul gioco verbale assegna apparentemente alla letteratura una libertà che è negata alla fotografia, è anche vero che, come lo stesso Baudelaire sapeva tacendo, una soddisfacente espressione della soggettività è possibile, in letteratura, solo attraverso una precisione oggettiva, fotografica, di ciò che si vede come di ciò che si sente. Il tormento di ogni scrittore matura in fondo da questo bisogno di fredda precisione, che la fotografia riesce a soddisfare, quando è puro documento, senza alcuno sforzo, meccanicamente, trovandosi a manipolare l’alfabeto universale delle immagini, piuttosto che quel mondo di instabili convenzioni che è il linguaggio, nel quale ogni scrittore è inscritto di epoca in epoca secondo le decisioni di quell’epoca, che lui lo voglia o meno. La libertà della scrittura è quindi apparente almeno quanto il debito contratto dalla fotografia con la realtà. Nessuna delle due è veramente libera.

A chi passi il testimone, e perché?

A Fausto Podavini, perché lo ammiro.

Intervista a cura di Marco Benna

ENGLISH VERSION

From Giovanni Marrozzini’s website: “Giovanni was first born in Fermo in 1971. The second time around he was reborn in Malta in 2001 thanks to his friend Andrea, who gives him a poem as a gift. Finally he was reborn again in Zambia in 2003 after a cerebral malaria infection. As a professional, he takes photographs in the name of passion and expressive creativity. He panders to the stories he comes across with and helps them escape labyrinths. He meets the Fairy Godmother in Argentina and Moses in Camerun. He lives in a trailer for a year without showing any relevant signs of mental instability (or so he thinks). He’s stubborn, instinctive, enthusiastic. He has three treasures: Mary, Leone and Francesco - that’s the rigorous yet temporary height order. His beloved dog, Ulisse, left for good when his owner returned from ITAca."

Narration has always been a very strong element in your photography - to the extent of combining stories of two or three photos to build up a geography of todays’ Italy in your work Itaca Storie d’Italia. What do you think the meaning of being able of narrating is?

It’s about extracting an experience from the flow of time. It happens by searching through its images for a symbolic link that simultaneously serves as plot and meaning of the plot.

All your photographs feature some kind of human element, be it a part of the humans’ body or signs of their passing by: why continue narrating Mankind through photography?

Why not?

Some of the videos shot during your ITAca journey are now collected on ITAca Storie d’Italia YouTube channel: Have you ever released or are you planning on developing a multimedia project? What’s your take on the integration between photography and multimedia?

When there’s a lack of time for a project to gush over in depth, I believe the integration between photography and multimedia is efficient, because it answers the reigning need to speeding up the fruition process. Multimedia facilitates our ability to absorb a story in a very short spam of time - perhaps to the detriment of more incisive reflection and pondering.

Falene tells the visual story of an institute for the blind and visually handicapped persons in Ethiopia. I assume you established a different relationship between the “observer” and the “observed”, which is usually based upon a reciprocity of looks: how did you relate to them? Did their condition influence your photographic style?

At first I was surprised at how it all functioned according to a logic that’s become clear to me now only - as if people were being moved around through invisible strings that created a sort of carousel. Their movements were graceful and choreographic. I watched them carefully: hands slightly removed from the body, wary and never a single accelerated step. They would speak in a low voice, they were affectionate and they would easily sense my astonishment - I could tell by the light tilting of their head and hands. They were grasping for signals, scents, information… After a few minutes of hesitation they would burst out in an empathetic and accepting smile. They got close to my camera more than once: only after realizing it was nothing but a piece of iron they would throw themselves at me, and touched me and embraced me. I couldn’t say how their minds pictured the image of my persona, though. Whilst touching me they would whisper one to the other, as if they were building up a picture of me altogether. Perhaps they went deeper than I managed to on the occassion.

You're shooting both in film and digital - perhaps using two slightly different approaches. Could you tell us about it?

The use of film makes the whole experience “more precious”, because you really perceive the work of time and the sense of limitation. Click after click you get to the end of the film. As the day’s gone by labeling each film, you have time to digest the whole visual experience. Imagination, passion, memory and patience then kick in. Eventually the darkroom will pass the (sometimes astonishing) verdict.

In several of your reportages you’ve established a very intimate relationship with people. How does this happen during your work?

Telling about a person is a real challenge. The main difficulties lie in the ability to make each other permeable enough.

You communication (see Facebook) is imbued with a kind of approach to your job where travel seems crucial. At least, that’s our impression - given that not only do you plan trips and experience them thoroughly, but you also describe them in full detail (with itinerary maps, backstage photos and pictures of vehicles, etc). What’s the relationship between your dimension as a traveller and your photography?

I auto-invite myself to a travel that resembles me a lot. I highlight only those unknown elements of myself that the trip unveils. That’s my poetic answer. More prosaically, I’ll just say that any given photographer has to travel because most clients require them to.

We understand you’re preparing a long trip across the African continent from Egypt to Cape Town: could you give us some sneak previews about this project?

It’s a very ambitious project I’ve been working on for the past 6 months. To avoid bad luck I’d rather not discuss it for the moment, though…

How do you prepare for a reportage or a photographic work?

a) I deepen the topics I’m going to deal with;

b) I define the possible timetable for the concrete realisation;

c) I choose the most fitting camera for the specific shooting;

d) I contact all the locals who’ll turn out to be my guides throughout the journey;

e) I ask for a deposit;

f) Often no deposit is paid hence the whole trip is postponed;

g) I get pissed off.

Your recent work ITAca (click here for the video of its opening) proves a particular photographic eclecticism - in terms of the ability of shooting by drawing from a number of photographic languages. Where does your visual and aesthetic formation come from and how does it develop?

I’ve never attend any photographic school, thus I’ll say it was born on 12th September 1971 and it’s been developing for 42 years.

We’re absolutely captured by the density of the sight and the richness of hues - two of the most prominent features of your work. What do you accomplish through photography and what does photography do to you?

I wouldn’t know. You pose difficult questions! What do I accomplish with photography? I narrate about myself. What does photography do to me? It listens to me.

We understand you’re particularly keen on the relationship between literature and photography. Could you tell us something about that?

All writers are shaken by photography and usually all photographers are moved by the charm of literature. Amongst others, Baudelaire failed photography tout court. He described it as an incapable and inadequate (not to say contrary) tool for representing the expressive world of art. If the sovereignty over the five senses and on the verbal game appear to invest literature with a freedom that’s generally denied to photography, there’s something Baudelaire purposely kept unsaid that is equally true: literature has the chance of a satisfactory expression of subjectivity only to the extent that it provides objective, photographic precision to what is being seen and felt. Every writer’s agony originates from this need for cold precision that photography succeeds to full fill. In case of a pure document photography achieves that urge effortlessly and mechanically by manipulating the universal alphabet of images, instead of dealing with a world of such unstable conventions as writing. When it comes to literature each writer is (willingly or unwillingly) inscribed within a certain era according to the decisions of the era itself.

Therefore the freedom in writing is merely as apparent as the debt photography contracted with reality. Neither is truly free.

Who are you going to pass the baton to? And why?

To Fausto Podavini, because I admire him.

The articles here have been translated for free by a native Italian speaker who loves photography and languages. If you come across an unusual expression, or a small error, we ask you to read the passion behind our words and forgive our occasional mistakes. We prefer to risk less than perfect English than limit our blog to Italian readers only.

Leave a Reply