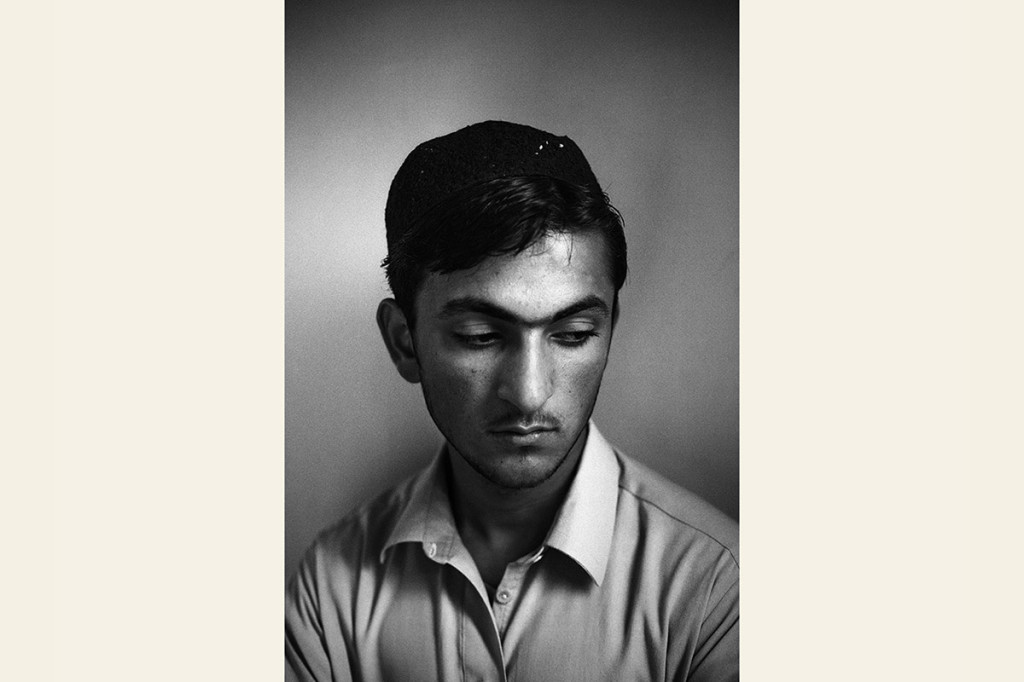

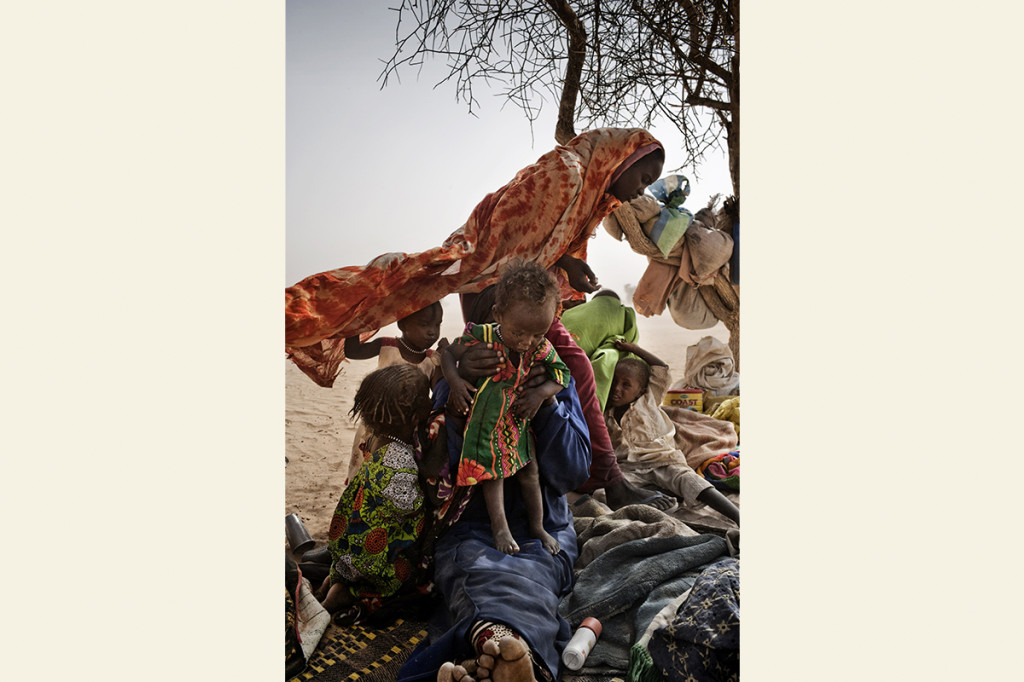

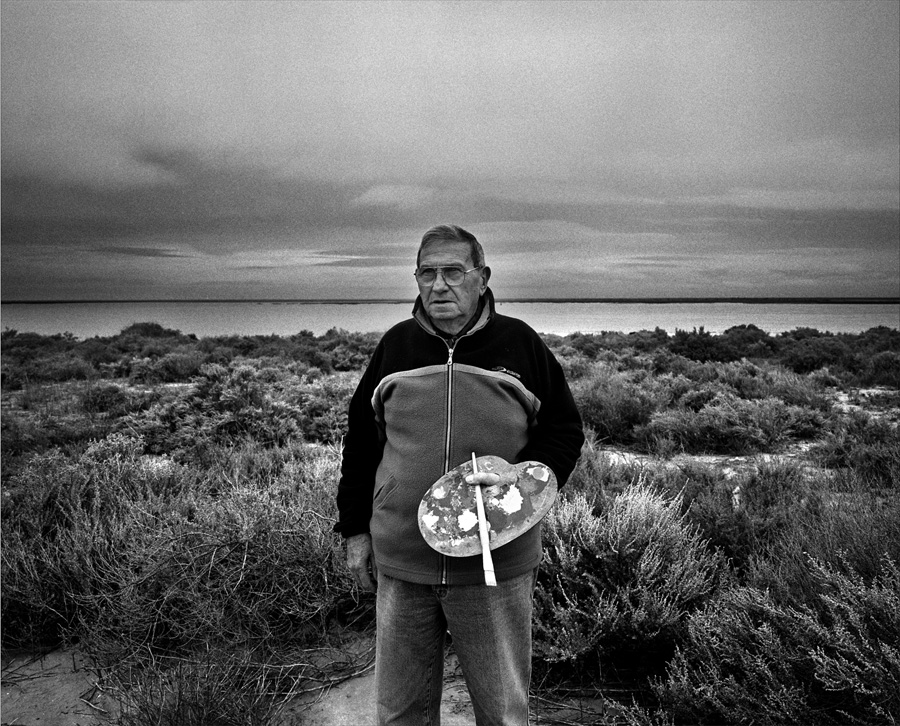

Nato a Roma nel 1979, Massimo Berruti interrompe gli studi di biologia per dedicarsi alla fotografia. Attivo come freelance dal 2004, nel 2005 entra a far parte dell'agenzia Grazia Neri. Con le sue immagini ha documentato storie dall'Italia, Europa, Vicino Oriente, Africa, Asia e USA. Negli anni ha costruito un rapporto privilegiato con il Pakistan e la cultura pashtun, dei quali ha raccontato il coinvolgimento e gli esiti della "guerra al terrorismo". Molte di queste immagini sono poi confluite in "The Dusty Path".

Con i suoi reportage Berruti ha ricevuto numerosi premi e riconoscimenti, da ultimo il Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund.

Dal 2008 è parte di Agence VU.

Per diverso tempo hai concentrato il tuo lavoro sul Pakistan: perché questa scelta? È un modo di parlare - attraverso il Pakistan - anche di altro o c’è qualcosa che ti lega a questo Paese e alle sue genti?

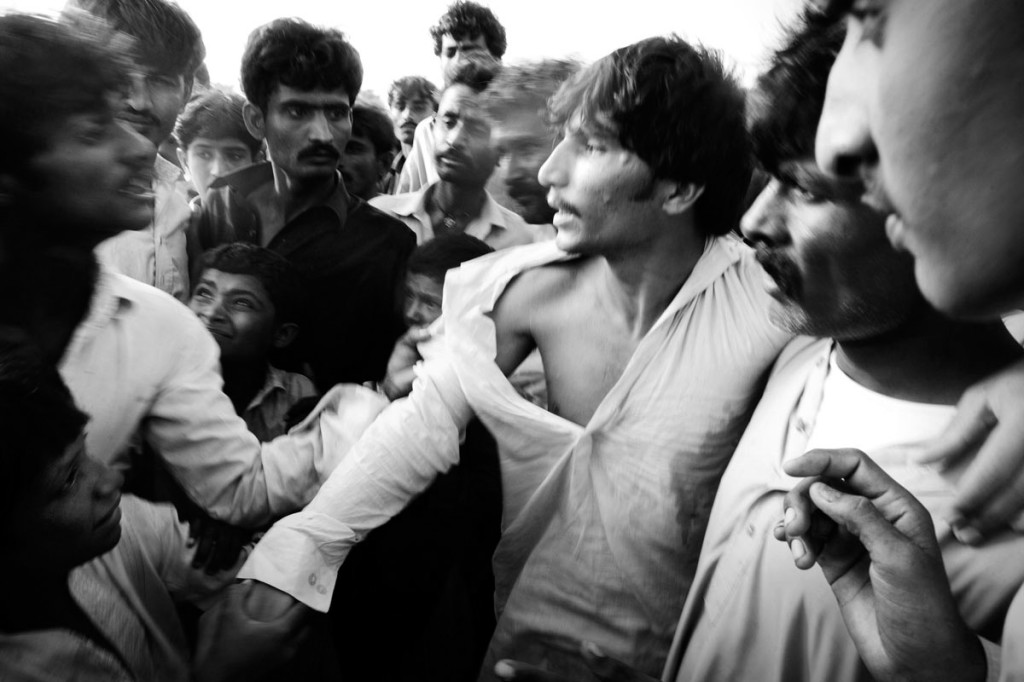

L’affezione a questo luogo c’è ed è forte, ma è venuta dopo. Per me il Pakistan era principalmente il terreno ideale per narrare quella che reputo sia una delle principali piaghe del Terzo millennio, quell’epopea infinita e grottesca che è la guerra globale al terrorismo.

Più volte hai dichiarato, in diversi modi, che il tuo lavoro realizzato in Pakistan, Lashkars, tende a restituire un’idea dei pashtun diversa da quella che spesso se ne ricava dalla vulgata occidentale. A noi sembra che questa sia una scelta che potremmo chiamare politica. Se così è, che rapporto c’è tra una scelta politica e il fare fotografia?

Non volevo tanto restituirne un’idea “diversa”, quanto una “più giusta”. Credo che quasi tutto ciò che facciamo sia più o meno direttamente connesso alla nostra visione della vita. Da come impostiamo la nostra quotidianità al nostro sistema di valori. Chiaramente le mie scelte da fotografo non sono da meno. Se questa naturale tendenza si può definire come fare politica non so. Ci sono molti rappresentanti di questa “arte” che si interessano alla fotografia come fine e non come mezzo. A me interessa soprattutto come mezzo. In questo senso credo che fotografia e politica possano avere un dialogo e magari anche un rapporto privilegiato.

Nell’affrontare le cronache pakistane, tocchi questioni particolarmente spinose, al centro di intrecci internazionali che intercettano le guerre in atto in quelle zone del mondo, guerre che sono le guerre del nostro tempo. Sembra che tu voglia andare vicino alla loro logica profonda (questo è quello che ci è rimasto dall’approfondire il tuo lavoro, ndr) passando però dalle storie delle singole persone, spesso ai margini delle nostre rappresentazioni (come in Lashkars) ma anche messe ai margini proprio dalla guerra (come in Hidden Wounds, o come nel lavoro che hai intrapreso sulle famiglie degli scomparsi). C’è una dimensione "rivelatrice" nel tuo lavoro che non ci pare solo fotografica. È così?

Sinceramente non credo. Non credo di svelare nulla di particolare, onestamente. Spesso però, ciò che più si sottrae alla nostra vista - e quindi alla nostra comprensione - è proprio ciò che si nasconde sotto al nostro naso. Io per certi versi ho avuto forse un po’ la pretesa di andare a spulciare l’ovvio, quello che tutti sanno, o meglio, credono di sapere. Nel 2008 ho mosso i miei primi passi in Pakistan, ed erano già sette anni che eravamo immersi in questa guerra.

Tutti pretendevano di sapere bene come stavano le cose, chi aveva fatto cosa, come e perchè. Io quelle certezze non le avevo, e non le ho. Ora almeno mi sono fatto un’idea.

A me piacerebbe solo che su questioni importanti e fondamentali ci si ponesse, almeno, qualche domanda in più. Spero in un risveglio del senso critico o almeno in quello di auto osservazione. Sarebbe un onore poter dare un piccolo contributo in questo senso.

E come fa la fotografia a reggere questa complessità?

Bella domanda. Si va per tentativi, ma non saprei dire se il mio lavoro riesca a sollevare anche solo una piccola parte dei dubbi che vorrebbe.

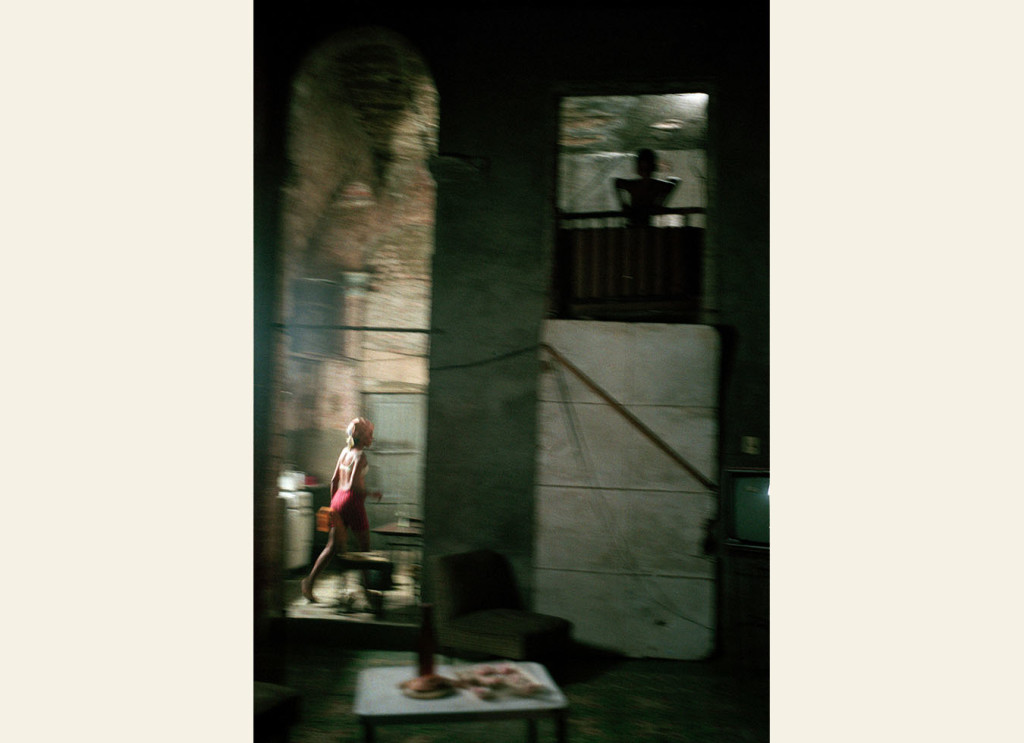

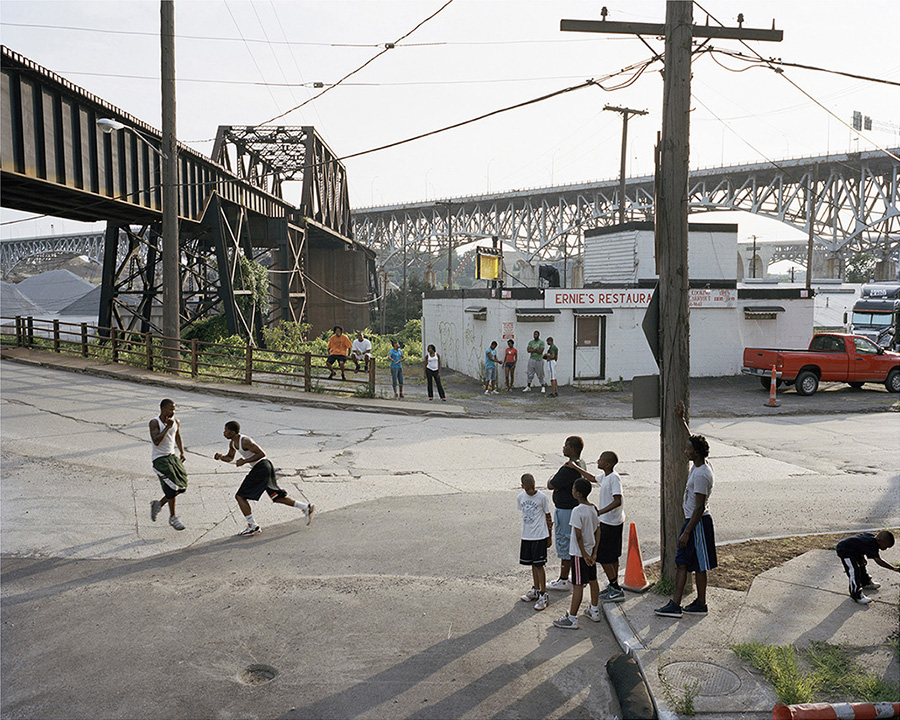

Circa 10 anni fa hai vinto un World Press Photo con il lavoro Residence Roma: credi che la fotografia possa incidere nei processi sociali? Se sì, come?

La fotografia fa parte dei processi sociali da quando esiste, e nel bene o nel male continuerà ad esserlo finché esisterà. Basti vedere come e quanto si investe in immagine oggigiorno. La comunicazione per immagini è alla base dell’ingegneria sociale. Quale modo migliore per comunicare concetti semplici senza bisogno di traduzioni? L’immagine entra direttamente in relazione con la sfera istintiva, limbica dell’individuo, e per questo sortisce degli effetti più stabili e duraturi. Considerata la moltitudine di immagini da cui siamo bombardati come spesso la futilità delle loro motivazioni, spero ci sia ancora spazio per divulgare intenti meno particolari e interessati.

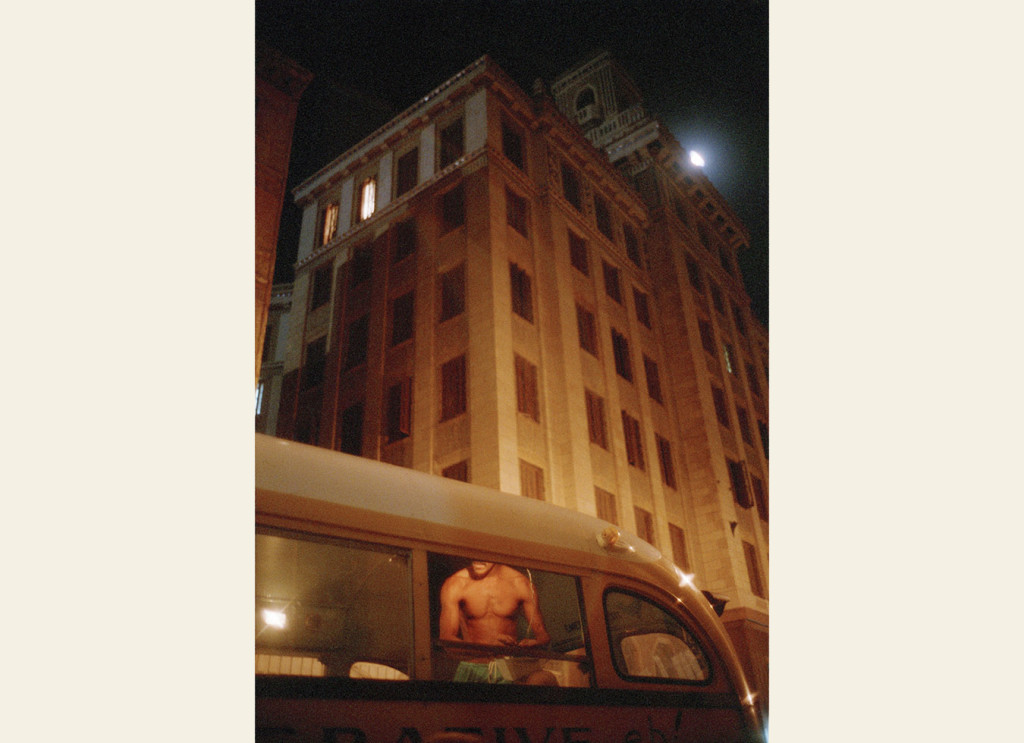

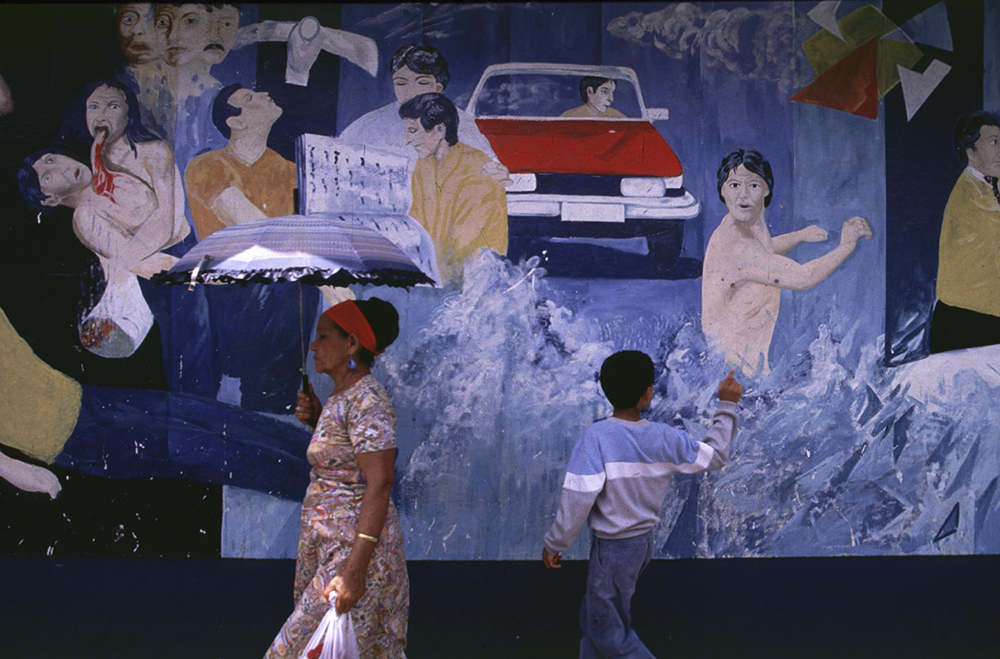

Il tuo lavoro Çapulcu sembra volere focalizzare l’attenzione non solo sulle manifestazioni contro il governo Erdogan, ma sul valore che i manifestanti sono riusciti a dare alla loro azione grazie ad un nuovo uso della parola Çapulcu. Anche questo lavoro sembra ribadire una “posizione politica”, è così?

I lavori che sento miei sono quei lavori in cui ho usato la fotografia come mezzo.

Credo che la politica sia una questione di scelte per cui, se vuoi, la fase politica di un lavoro inizia dalla scelta di affrontare un argomento piuttosto che un altro. Solo che avere una visione politica non vuol dire fare politica. Trovo abbastanza normale pensare che visione e fotografia sociale possano ragionare insieme. Mi sembra umano.

Se si volesse levare l’annosa obiezione sul fatto che il giornalismo debba essere asettico e imparziale, forse direi che questo è il dito dietro cui si può nascondere la vera faziosità.

Sempre in Çapulcu, è interessante la questione del rapporto parola e immagine. Nella presentazione del lavoro parli diffusamente dell’uso della parola çapulcu, cosa che nelle fotografie non ritroviamo. Come concepisci questo rapporto, parola e fotografia?

Le fotografie dovrebbero parlare da sole il più possibile, il testo serve a completare ciò che non si poteva o non si è riusciti a rendere per immagini. Do sempre un titolo ad una storia, ma di solito non includo il titolo nella sua rappresentazione. Fotografare scritte, a scopo comunicativo, raramente rafforza una fotografia nello sforzo di trasmettere i suoi contenuti. Çapulcu sono tutti i civili che ho fotografato, sono tutti coloro che hanno deciso di manifestare contro le politiche reazionarie e assolutiste del presidente Tayyip Erdoğan che li ha additati come tali.

Çapulcu vuol dire vandali.

Come procedi nel costruire i tuoi reportage? Puoi entrare nel merito con qualche esempio?

Non ho un vero metodo, le situazioni sono diverse: a volte devi soprattutto costruire una lunga rete di contatti, altre volte ti devi solo lanciare nel fitto della storia, essere accettato e rispettare le sue condizioni.

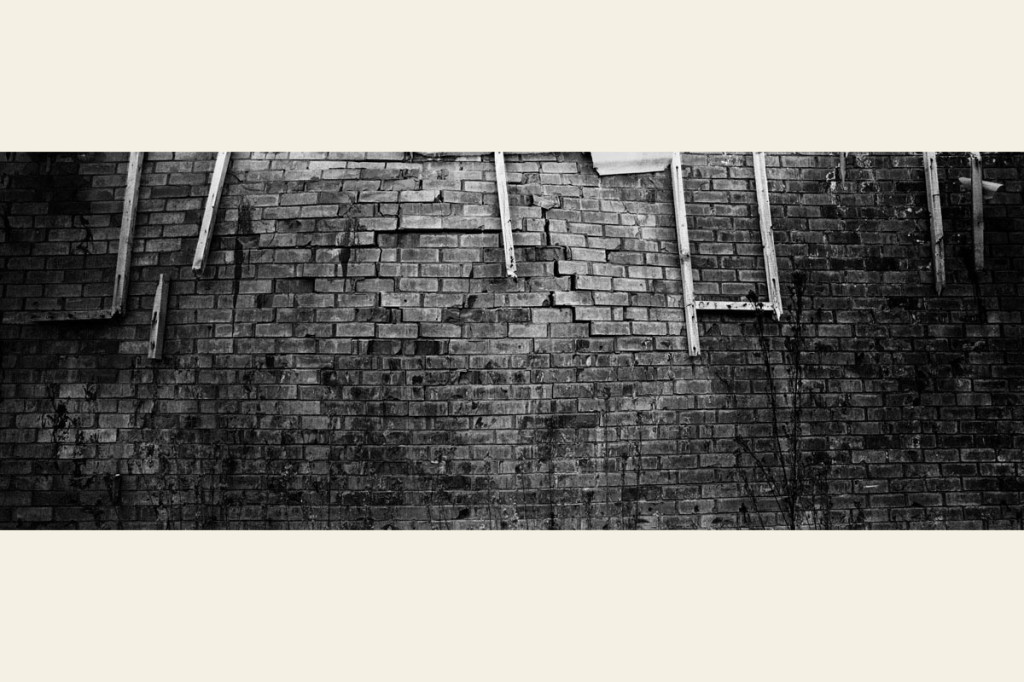

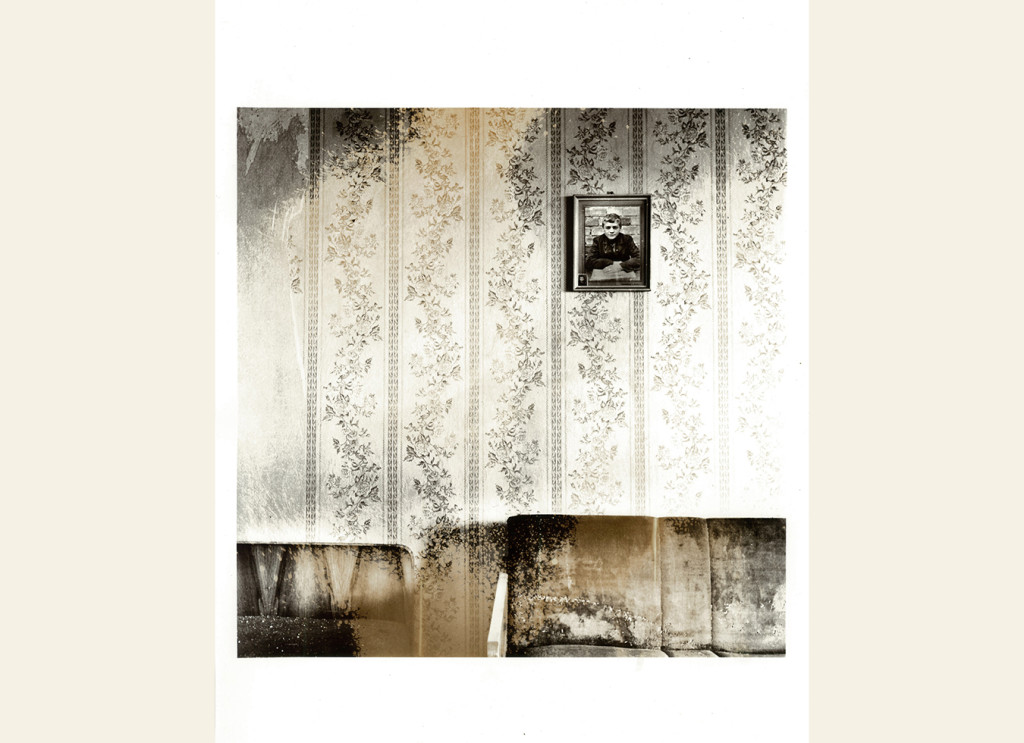

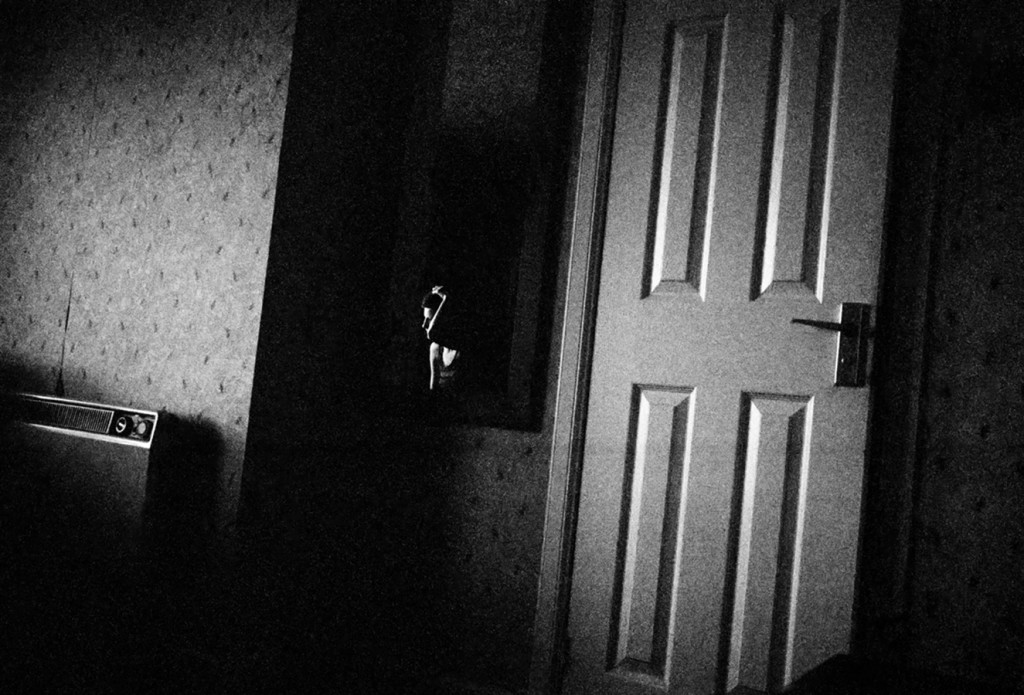

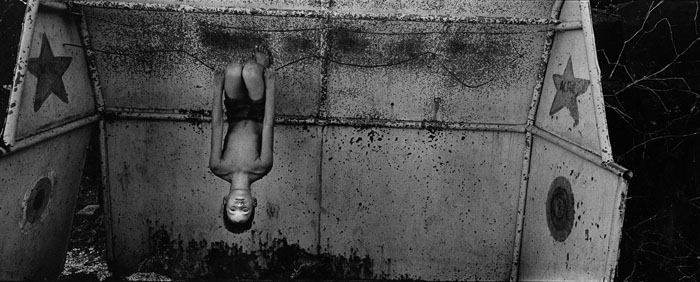

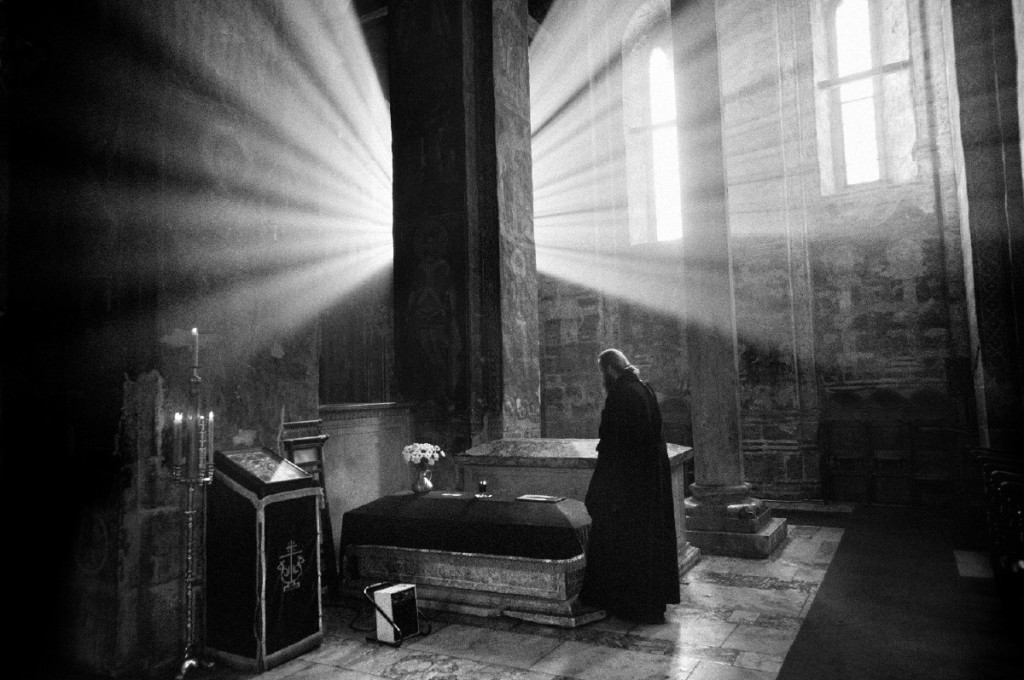

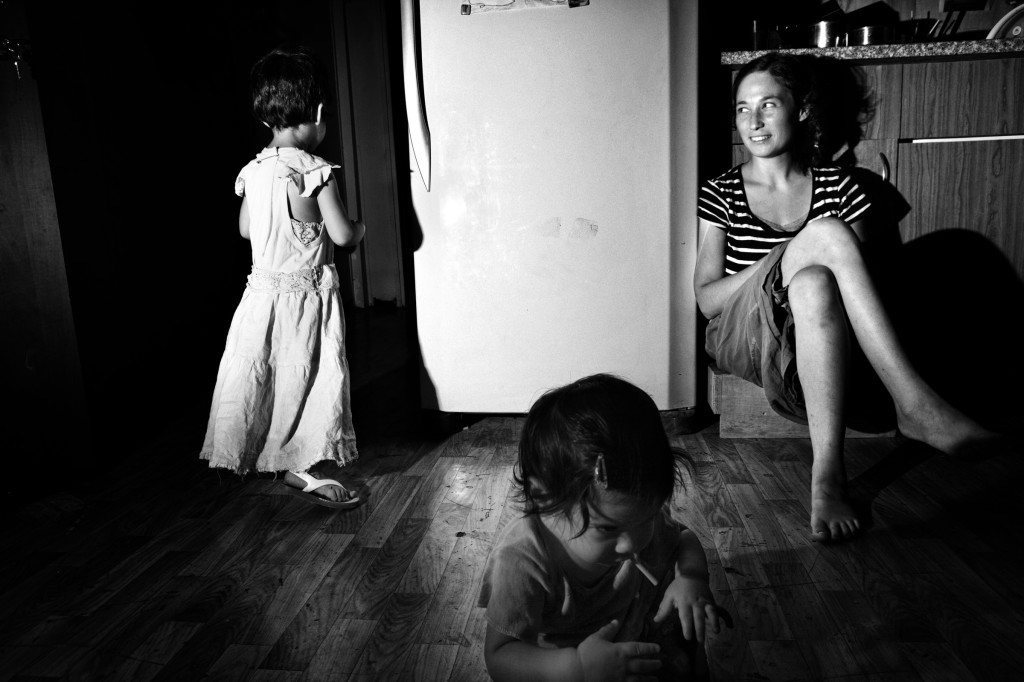

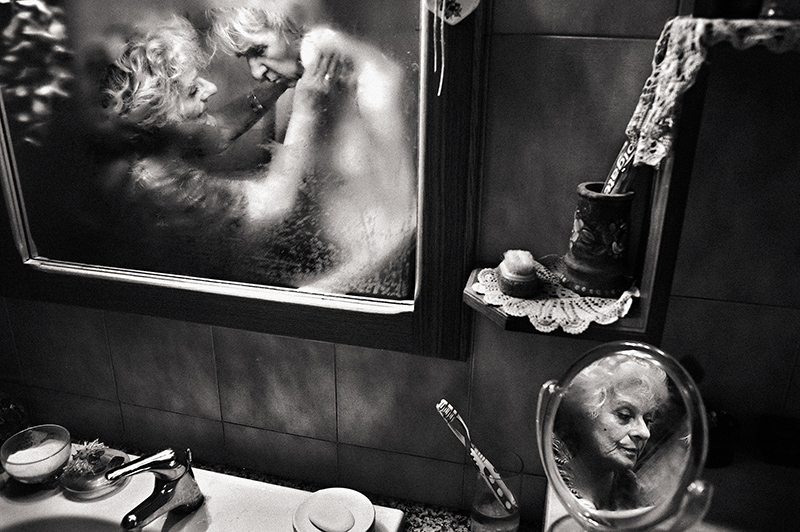

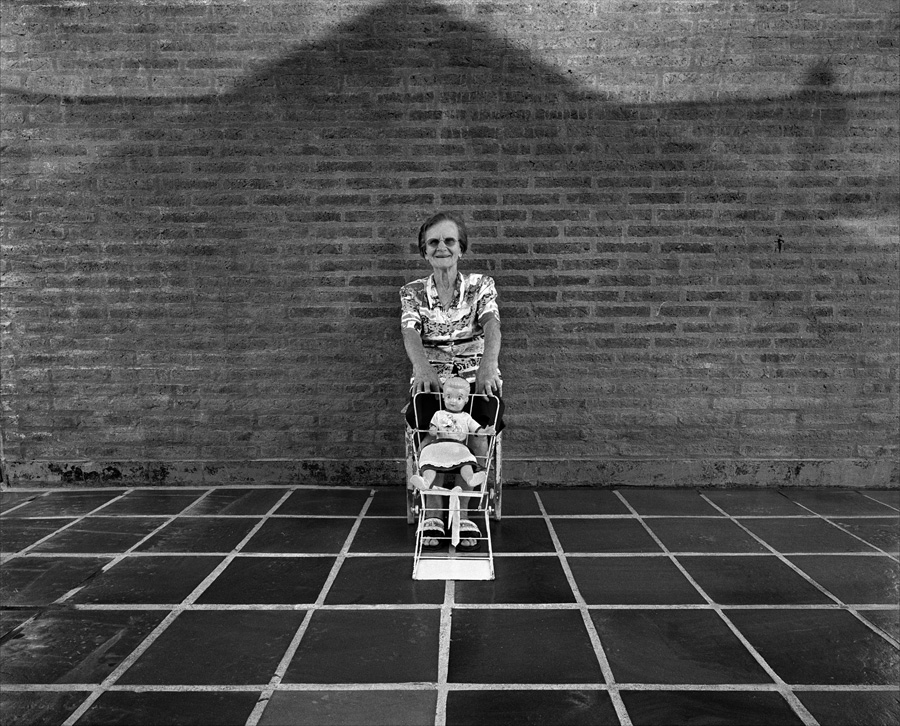

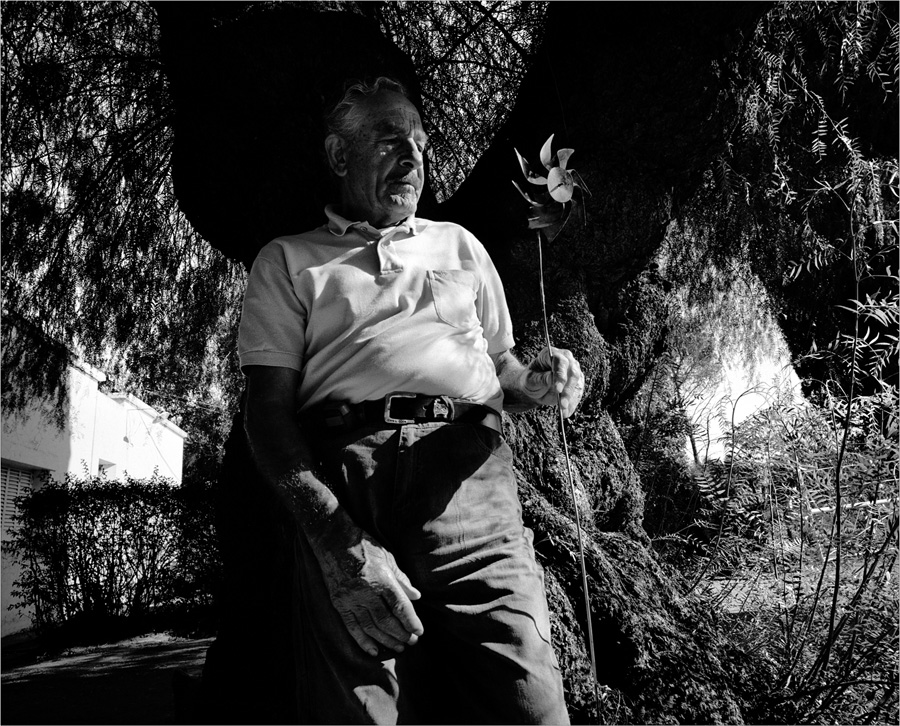

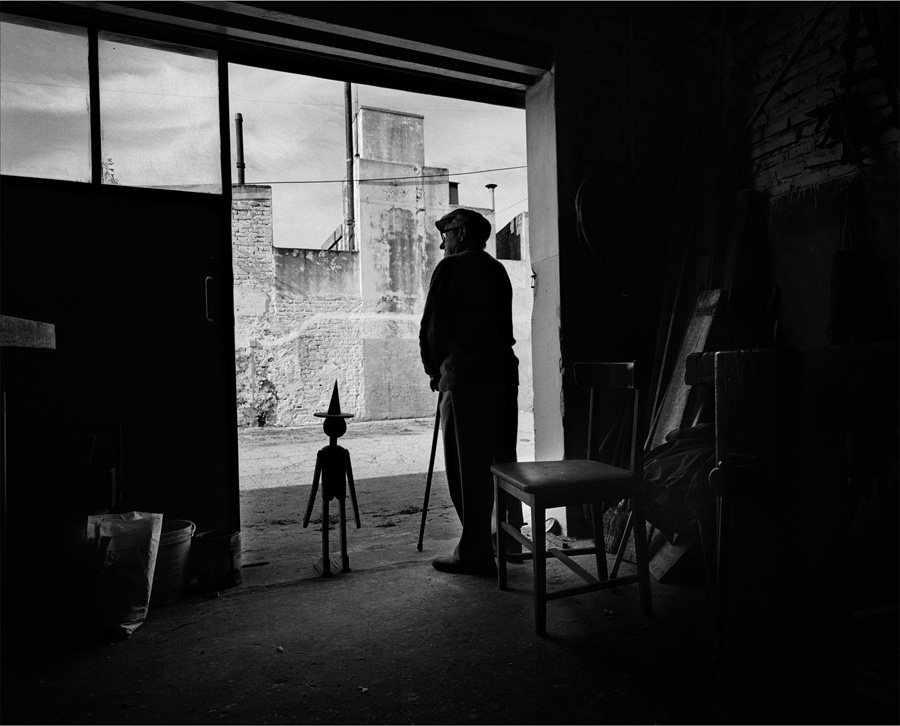

Perché la scelta di fotografare in bianco e nero? In un’intervista sostieni che il bianco e nero ti permette di «innalzare il discorso ad una visione più metaforica». A cosa risponde questa necessità?

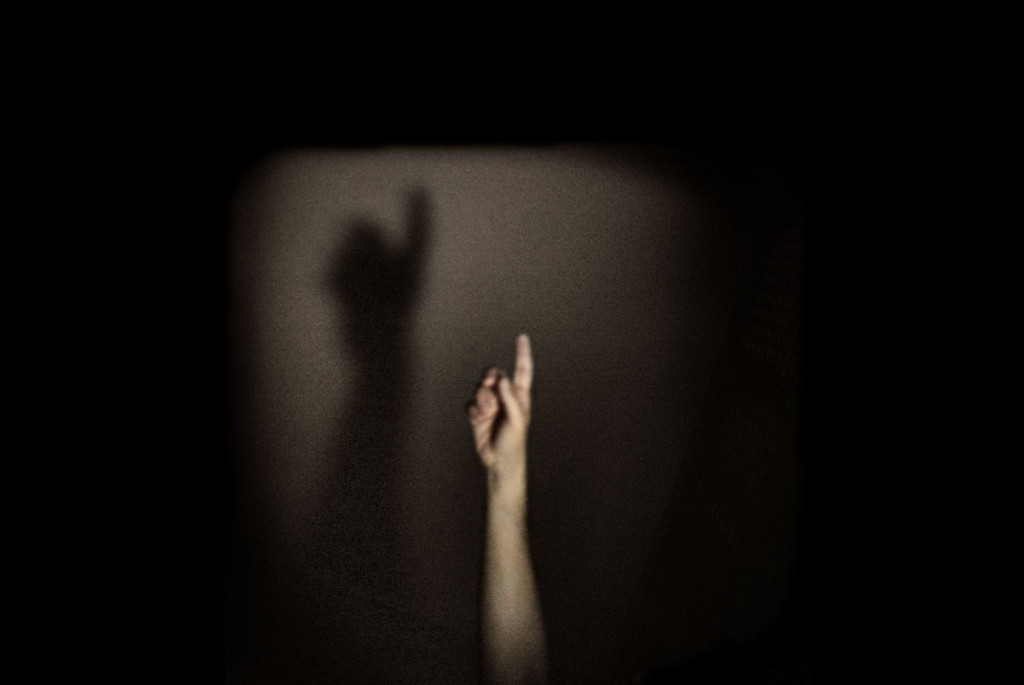

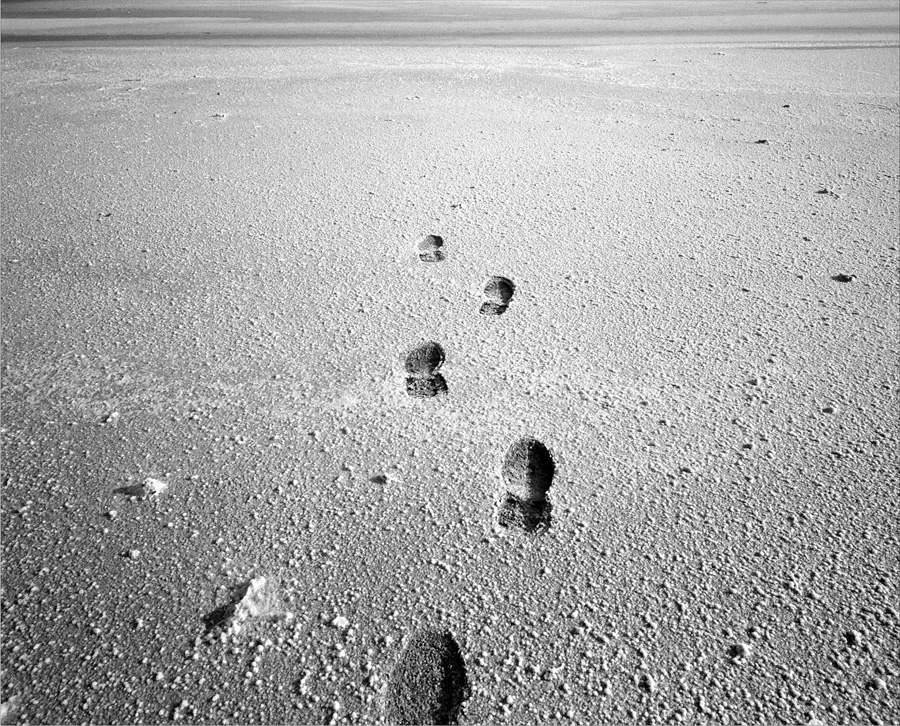

Dovevo essere ispirato dall’alto se ho detto questa cosa. Principalmente il bianco e nero mi libera da pesanti sovrastrutture estetiche per me legate al colore, che non mi sento sufficientemente capace di gestire. Per quanto riguarda invece la metafora e l’iconografia simbolica, è più semmai una ricerca, in cui il bianco e nero di sicuro mi aiuta, smaliziandomi. La storia dell’uomo è fatta di ripetizione, di storie che corrono e ricorrono - diverse e uguali tra loro - nel tempo. L’iconografia come la metafora, permettono di valicare i limiti fattuali e temporali della singolarità. Sono quelle immagini semplici, dirette e pulite, che perdurano e formano il nostro substrato culturale.

Sostieni che l’uso di uno o al massimo due obiettivi permetta una coerenza visiva. Cos’è per te la coerenza visiva, e cosa è in grado di produrre? In sostanza, perché ricercarla?

La coerenza visiva, in senso ottico, è quella che parte dal nostro modo di percepire il mondo per immagini, attraverso i nostri occhi. Il nostro angolo, la nostra prospettiva, sono quelle e quelle rimangono.

Se devo raccontare una storia per immagini, specialmente se fotografie, sento il bisogno di rispettare quelli che sono i limiti ottici di chi la osserva. La coerenza visiva diventa quindi parte integrante della narrativa. Nel caso contrario espongo il lettore ad una serie di approcci/linguaggi visivi che lo disorientano, e gli impediscono di poter vivere la storia come fosse “con i propri occhi”.

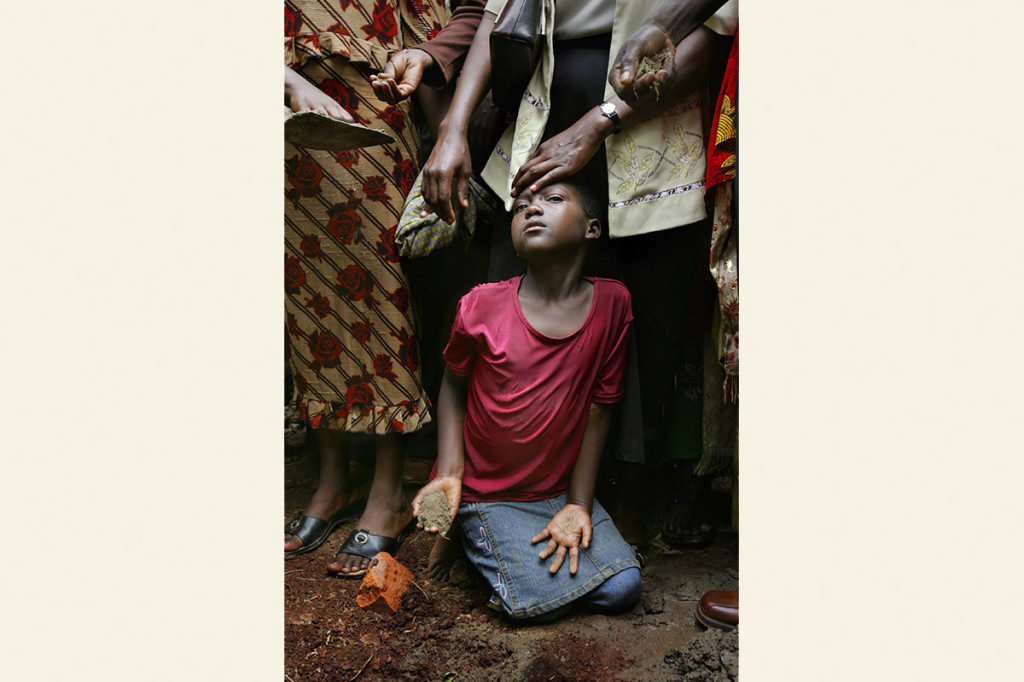

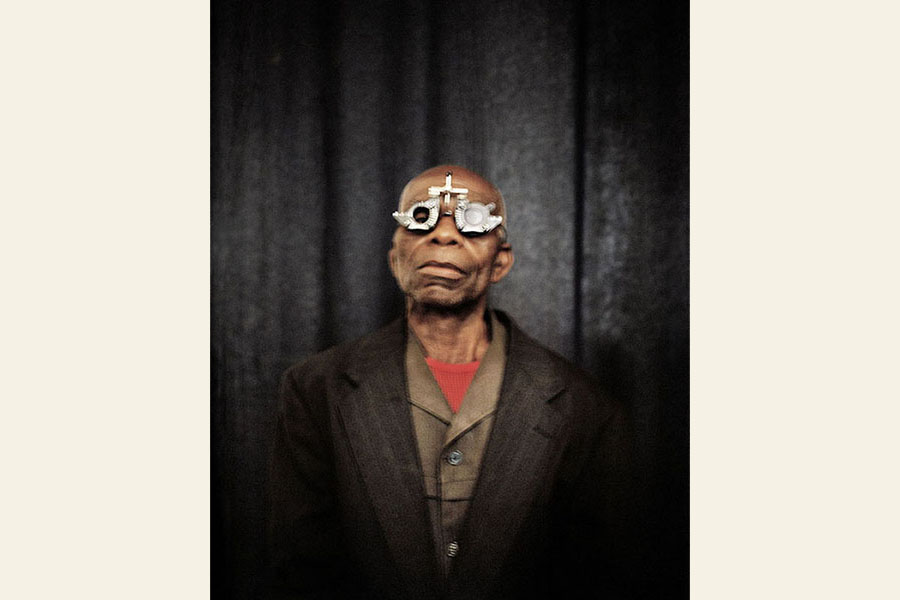

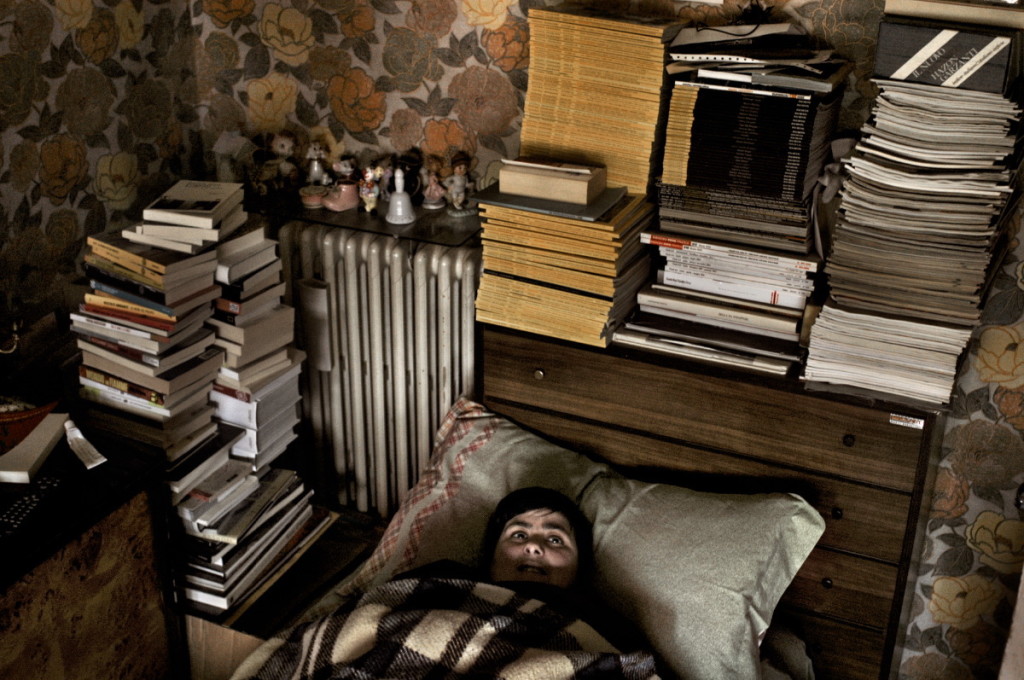

Con Lost in Kabul ci porti dentro la disperazione. Sono fotografie che ci mettono di fronte a qualcosa di cui non si ha esperienza, e che riguardano l’annullamento della persona. Come sai bene, nel dibattito sulla fotografia del dolore (per usare un termine ricorrente esemplificato dalla polemica Sontag vs Linfield) si mette severamente in discussione questo genere di fotografie. Cosa ne pensi?

Penso che la risposta sia un po’ figlia delle precedenti: non mi piacciono le dicotomie ma per semplificare si potrebbe dire che è una questione di scelta tra la narrativa e la pornografia, per cui una scelta di coscienza, politica se vuoi. La fotografia è “rappresentazione” della realtà, non la realtà stessa: inutile ambirvi. Da una parte è il mezzo che lo impedisce, e il fotografo come essere umano dall’altra.

Così come un giornalista che debba raccontare il dolore a parole usa la punteggiatura e forme lessicali o letterarie appropriate, ritmando il racconto a sua discrezione, così il fotografo usa il soggetto, l’inquadratura, la luce e l’istante. Ogni singola foto è il frutto di una selezione a monte e a posteriori, e della combinazione di tutti questi fattori messi insieme. Può corrisponde alla definizione di reale? Chiaramente è molto improbabile.

Accantonato quindi il “mulino a vento” della fotografia come riproduzione della “realtà”, credo che quello che si debba pretendere nell’ambito di quella documentaria, sia piuttosto un “racconto” giusto e onesto oltre che, appunto, ben documentato. Io credo che chi guarda abbia gli strumenti per saper discernere.

La narrativa è una parte fondamentale del processo, senza di essa non potremmo capire il caos di ciò che ci accade intorno.

Quel lavoro a Kabul lo sento abbastanza lontano, ero fresco ancora di fotografia e più impressionabile di adesso. Era una delle primissime volte che mi affacciavo a tale miseria.

È indiscutibile che questi fattori abbiano influenzato la mia percezione. C’è un’immagine di quel lavoro che mi sono interrogato a lungo se fosse giusto mostrare. Quando la rivedo ancora me lo chiedo. Me lo chiedo perché è un’immagine estremamente cruda, violenta per gli occhi, per lo stomaco, ma non esattamente immediata. Forse è per quella sua mancanza di immediatezza che è ancora li. Perché in qualche modo, forse, si fa un po' “metafora” e spero non oltrepassi la sottile linea rossa del cattivo gusto.

Quella credo sia l’unica immagine per cui ho ancora dubbi di questo tipo.

Penso che “troppa realtà” nella rappresentazione del dolore rischi di tramutarsi in pornografia, quella pornografia che sciocca e anestetizza, ed è questo da cui cerco veramente di stare più alla larga possibile.

Sei uno dei fotografi che ha fondato Zona e che vi partecipa attivamente: cosa vi ha spinto a creare questa piattaforma?

Zona è un progetto in divenire, un esperimento di emancipazione editoriale. Siccome sappiamo tutti le situazioni in cui versa l’editoria, cerchiamo formule di sostenibilità. Abbiamo alcuni progetti aperti che ambiscono a quell’indipendenza, un’indipendenza che reputiamo fondamentale.

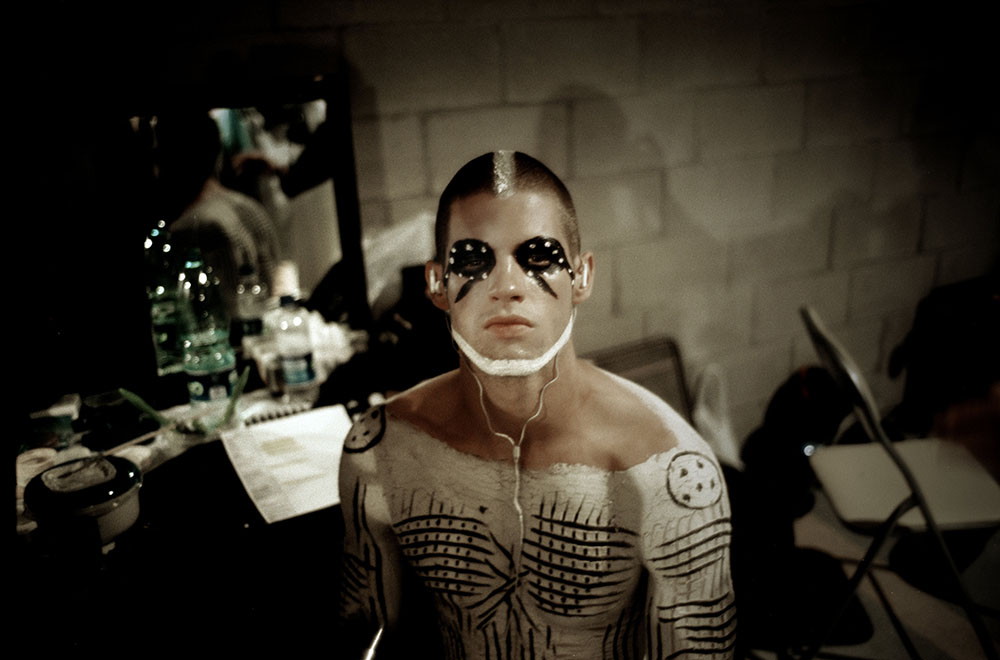

Realizzi anche lavori su commessa commerciale: come ti poni verso questa attività fotografica, considerando che il tuo lavoro di reportage è fortemente caratterizzato nello stile, nella scelta dei temi e nel lavoro di preparazione? C’è qualcosa di questa esperienza che riporti anche nei lavori commerciali?

Per i lavori commerciali è necessario cercar di fare tabula rasa. Quello che magari ci si può portare dietro è la curiosità, cercando di appassionarsi sempre a ciò che si sta facendo. Non mi capita mai di fare foto in studio, di solito vengo scelto per le qualità di improvvisatore e la cosa mi fa sentire a mio agio.

Che rapporto hai con la narrazione? Imposti i tuoi lavori pensando anche ad un livello narrativo?

Non parto con le mani avanti, l’approccio narrativo parte a storia iniziata. Dopo aver studiato una storia, cerco di immaginarla, di esserne protagonista, e percorrendola a partire da quei frammenti che ho potuto apprendere durante un primo approccio puramente giornalistico, cerco di immaginare quelli che possono esserne gli aspetti irrisolti o meno rappresentati. Aspetti che possono migliorare la comprensione di una situazione o di un avvenimento. È un tentare continuo, in cui la casualità e l’imprevisto mantengono comunque un ruolo a volte risolutore.

Ti occupi direttamente dell’editing o lo affronti con l’aiuto di qualcun’altro?

Assolutamente da solo, sarebbe un incubo altrimenti. Quando poi arrivo a dover scegliere una serie ristretta di immagini per intenti specifici, quali una mostra ad esempio, chiedo a volte consiglio a colleghi e amici che ammiro e stimo.

La storia del bianco e nero comprende anche una storia del lavoro in camera oscura. Come affronti oggi la fase di post-produzione, con quale approccio?

Un po’ come alla scuola di fotografia, faccio tutto io. Cerco di intervenire sempre meno, per quanto sia necessario perché i file delle fotocamere digitali sono piatti e standardizzati. La natura analogica della pellicola le conferiva opportunità plastiche che sono scomparse.

Riguardo alle polemiche che spesso si accendono intorno a questo tema, credo che una eccellente post produzione possa aiutare una foto, ma non inventarsela. Per cui, molto rumore per nulla.

Le manipolazioni invece, sono ben altra cosa.

Qual è la forma che secondo te restituisce meglio il tuo lavoro, ad esempio tra mostra, libro, multimedia?

Mi piacciono tutte e tre, si completano lavorando insieme. La fotografia ha parecchi limiti e usare diversi supporti credo possa aiutarla a completarsi per meglio affrontare tematiche complesse.

Come fotografo ti senti vicino ad altri fotografi, magari come tipo di scelte, di stile o di approccio? Qual è la tua formazione?

Mi sono avvicinato alla fotografia a 23 anni seguendo un corso convenzionato dalla regione Lazio. Non me ne ero mai veramente interessato prima ma avevo le idee abbastanza chiare.

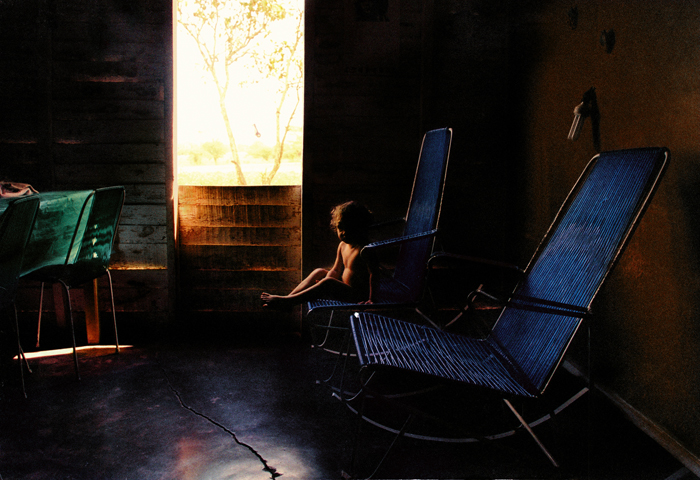

Vivendo a Roma, è stato molto utile poter andare a curiosare tra quei lavori che si potevano vedere su internet, su siti di agenzie formate da grandi autori come Magnum o VU. Mi sono appassionato a quella tradizione del bianco e nero che ancora mi porto dietro. Don McCullin, Philip Jones Griffiths, Salgado, James Nachtwey e Paolo Pellegrin, sono alcuni degli autori che amo di più. Amo molto anche autori a colori e li ammiro per la loro disinvoltura. Credo comunque che ciò che formi di più un fotografo sia la pratica, il fare fotografia. Ci sono tante cose che si deve imparare e gestire prima di fare anche un solo scatto.

Dove sta andando la tua fotografia?

Non lo so e non me lo chiedo, anche se mi rendo conto di trovarmi ad affrontare un cambiamento. Mi interrogo raramente al riguardo, preferisco stimolare l’intuizione.

A chi vuoi passare il testimone e perché?

A tanti e a nessuno, non ho un particolare prediletto.

Intervista a cura di Marco Benna

ENGLISH VERSION

Massimo Berruti was born in Rome in 1979. He quits studying Biology to dedicate himself to photography full-time. Working freelance since 2004, in

in 2005 he enters the Grazia Nery Agency. His photos tell stories from Italy, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia and the US. Over the years he’s built a special bond with Pakistan and the Pashtun culture, documenting the beginning and the outcomes of the “war on terrorism”. A number of these pictures later ended up in “The Dusty Path”.

Thanks to his reportage, Berruti has been awarded numerous awards and acknowledgements - the latest being the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund.

He has been part of Agence VU since 2008.

A great deal of your time and work is focused on Pakistan: why did you choose that? Is Pakistan a way of talking of something else or is there something that connects you to this country and its people?

There’s a strong affection for this country, but it came later. At first, Pakistan was mainly the ideal land where to tell one of the principal plagues of the third millennium, that is the infinite and grotesque epic of the global war on terrorism.

On manifold occasions and in different ways you’ve stated that your work in Pakistan, Lashkars, tends to give back an idea of the Pashtuns that’s different from what we usually get in the West. It seems to us that this choice could be deemed political. If that is the case, what’s the relationship between a political choice and photography?

I didn’t want to give back so much of a “different” idea [of Pashtuns], but a “more just” one. I believe that almost everything we do is more or less directly connected to our vision of life - from the way we set our daily routine to our system of values. Obviously my choices as a photographer are no less than that. I don’t know whether this natural tendency could be deemed “political”. Plenty of representatives of this “art” are interested in photography as en end, not as a means. As for me… Photography is most and foremost a means. In this sense, I believe photography and politics can build a dialogue and perhaps even a privileged relationship.

In dealing with Pakistani chronicles, you touch particularly sensitive topics. They’re the core of international plots that intercept ongoing wars in those areas of the world - the wars of our times. It seems like you want to get close to their deep logic (this is what we felt as we deepened your work) by using the stories of individuals who are often on the margins of our representations (see Lashkars) - or even put on the margins by the war itself (see Hidden Wounds, or the work you made with the families of the disappeared ones). There’s a “revealing” dimension within your work that doesn’t seem merely photographic to us. It that so?

Honestly, I don’t think so. I genuinely don’t think I’m unveiling anything in particular. However, the thing that escapes our sight (and our comprehension, too) the most is often the thing that stays hidden right before our nose. In a way, I’ve claimed to tear down this veil of obviousness, [and] dismantle what everyone knows or what they believe they know. I first ventured to Pakistan in 2008, [a country that was] already 7 years into this war. Everyone claimed to know how things went just perfectly, who did what, how and why. Me… I had none of those certainties, and I still don’t have any. But at least I have an idea now.

What I’d really wish for is that when it comes to fundamental and important affairs people posed just a few more questions. I confide in an awakening of the critic sense, or self-observation at least. Giving a small contribution this way would be an honor.

And how does photography manage to keep up with this complexity?

Good question. One tries and tries again, but I wouldn’t know whether my work is really capable of raising even just a small part of the doubts it’d want to.

Some 10 years ago you won a Word Press Photo award with your work Residence Roma: do you believe photography can leave a mark in social processes? If so, how?

Photography has been part of social processes ever since it came into existence - and as long as it exists, it will keep being so, for better of for worse. Simply consider how and how much is being invested on photos these days. Communicating via images is the basis of social engineering. What better way to convey simple concepts without the need of translations? Images enter a direct relationship with the instinctive, “limbo-esque” sphere of the individual, and that’s why they produce more stable and durable effects. Considering the multitude of images that bombard us as much as the futility of their reasons, I hope there will still be room to spread less particular and more captivating intents.

Your work Çapulcu seems to be focusing not only on the demonstrations against the Erdogan government, but also on the value that protesters managed to give to their action thanks to a new use of the word Çapulcu. This work seems to confirm a “political siding”, too. Is that so?

The works I feel like they're truly mine are the works where I used photography as a means.

I think politics is a matter of choices. So, if you will, the "political" phase of a work begins with the choice to face a certain topic instead of another. But having a political vision doesn’t mean “doing politics”. I think it’s quite normal to think that [a political] vision and social photography can reason together. It seems just human to me.

If we were to remove the long-standing objection to the fact that journalism should be aseptic and impartial, perhaps I’d say this is the finger behind which true bias hides.

Sticking to Çapulcu, the relationship between text and image is particularly interesting. In the presentation of your work you diffusely talk about the use of the word Çapulcu - which is something we don’t find in your photos. How do you conceive this word/photography relationship?

Photos should speak by themselves as much as possible. Texts are there to complete what you couldn’t or didn’t manage to express through photos. I always give a title to a story, but I usually don’t include the title in its representation. Photographing writings for a communicative purpose rarely reinforces the photo’s effort to convey its content. Çapulcu are all the civilians I took photos of, all the people who decided to protest against the reactionary and authoritarian politics of president Tayyip Erdogan, who held them up as such. Çapulcu means vandals.

How do you proceed in building your reportages? Could you give us a concrete example?

I don’t really have a true method. Situations are different. Sometimes you’ll mostly have to build a long network of contacts; other times you just have to through yourself right into the story, be accepted and respect its conditions.

Why did you choose to shoot in black & white? In an interview you stated that black & white allows you to “elevate the narration to a more metaphorical vision”. What does this urge answer to?

I must have felt inspired by high above to say such a thing. What black & white mainly does is liberating myself from heavy aesthetic superstructures that I feel connected to colors - and that I don’t feel sufficiently able to manage. As for the metaphor and the symbolic iconography, it’s more of a research where black & white helps me with no doubts, by teaching me a thing or two. Men’s history is made of repetitions, of stories that chase one another over time - stories that are different and identical in themselves. Iconography, as well as metaphor, allow to go beyond the factual and temporal limits of singularity. It’s those simple, direct and clear images that endure and form our cultural basis.

You maintain that using one or two lenses at the most allows for visual coherence. What is visual coherence for you, and what is it capable of producing? That is, why look for it?

From an optical level, visual coherence is that part of our way of perceiving the world through images, through our eyes. Our angle and perspective are what they are, and they remain what they are.

If I want to tell a story with images, especially photographs, I feel the need to respect the optical limits of the viewers. Therefore visual coherence becomes an essential part of the narrative. Otherwise I’ll expose the viewer to a series of visual approaches/languages that will disorient him, and will eventually prevent him to live the story as if it were [told] “through his eyes”.

With Lost in Kabul you lead us into the desperation. These photos put ourselves before something we have no experience of, dealing with the annihilation of the individual. As you know, the debate around “the photography of pain” (using a vastly recurrent term in the debate between Sontag and Linfield) puts these photographs in discussion severely. What do you think about it?

I think this answer can be deduced from my previous ones: I don’t like dichotomies, but to put things simply you could argue that it’s a question of choosing between narrative and pornography. So it’s a moral, even political choice, if you will. Photography is a “representation” of reality, it’s not reality itself. There’s no point in aiming at that. On the one hand, it’s the means that prevents it; on the other, it’s the photographer as a human being.

Just like a journalist who has to describe pain with words uses punctuation or the appropriate lexical and literary forms, giving a rhythm to his narration according to his will, similarly photographers use the subject, the framing, the lighting and the instant. Every single photo is the outcome of a selection that operates [both] at the root cause and at the bottom. It’s also the fruit of the combination of all these factors combined together. Can this really match the definition of what’s real? Clearly it’s highly unlikely.

So putting aside the “tilting at windmills” of photography as a reproduction of “reality”, I believe that what you should demand from documentary photography is a narration that is fair and honest, as well as properly documented. I believe viewers have the tools to be able to discern.

Narrative is a fundamental part of the process. Without it we could never understand the chaos of what happens around us.

As for that work in Kabul, I feel quite distant from it. Back then I was still a rookie at photography and much more impressionable than I am now. It was one of the very first times that I faced such misery.

These factors unquestionably influenced my perception. It took a lot of thinking on whether it was just to show a certain image of that work. I still wonder about that when I see it. And I do wonder because it’s a raw image - it’s violent to the eyes and to the stomach, but not exactly immediate. Perhaps it’s because of its lack of immediacy that it’s still there. Perhaps, somehow, you make a “metaphor” and I hope it doesn’t cross the fine line of bad taste.

That’s the only photo I’m still doubtful about on this regard.

I think that an “excess of reality” in representing pain risks to turn into pornography - that sort of pornography that shocks and anesthetizes. And this is exactly what I try to avoid at all costs.

You are among the founding photographers of Zona, and you play an active role in it. What led you to create this platform?

Zona is a work in progress, an experiment of editorial emancipation. As we’re all aware of the current state of the editorial world, we’re looking for sustainable ways. We have a few open projects aiming at that independence - a [level] of independence we deem fundamental.

You also work on assignment. What’s your position towards this photographic activity, taking into consideration that your work as a reporter is highly characterized in style, in choosing themes and the preparatory work? Is there something of this experience that you bring to assignments?

When you work on assignment it’s necessary to start from scratch. What you might take with you is curiosity, perhaps - and trying to always feel passionate about what you’re doing. I never happen to shoot in the studio. I’m usually chosen for my improvising skills, and this really puts me at ease.

What’s your relationship with narration? Do you construct your works bearing in mind a narrative level, too?

I never throw myself headfirst: the narrative approach starts once the story has already started. After studying a story, I try to picture it out, to be its protagonist, and go through it starting from the fragments I learnt during a first, purely journalistic, approach. I try and imagine the unresolved aspects, or the least represented ones. You except them to better the comprehension of a certain situation or event. It’s a constant trying where casualty and the unexpected keep playing a major role - which is often a conclusive type of role.

Do you follow the editing process yourself or are you assisted by somebody else?

It’s absolutely all on me - otherwise it’d be a nightmare. Then when I get to the point of choosing a selected series of images for specific intents, e.g. an exhibit and the like, I sometimes turn to trusted and respected colleagues and friends for advice.

The history of black & white photography is also a history of dark room work. How do approach the post-production phase today?

It’s a bit like at photography school: I do everything myself. However necessary, considering that digital camera files are flat and standardized, I try to intervene as little as possible. The analog nature of the film would provide plastic possibilities that have disappeared now.

As for the debates that often spring up around this topic, I believe an excellent post-production can help a photo, but it cannot reinvent it. So it’s a lot of noise for nothing, really.

On the other hand, manipulations are an entirely different thing.

What’s the form that you think best reflects your work, e.g. exhibitions, books, multimedia?

I enjoy all of the above. They complement each other when interacting together. Photography has a number of limits, so I think that using different media can really help complement it in order to better document complex topics.

As a photographer, do you feel close to other photographers - say in terms of choices, style or approach? What’s your education?

I approached photography at the age of 23 while attending a course sponsored by Regione Lazio. I’d never really felt drawn to it, but my ideas were quite clear. Living in Rome, it was very easy to browse through works online, on the websites of such great agencies as Magnum or VU - as they comprised big authors. I developed a passion towards that black & white tradition that I still hold on to now. Don McCullin, Philip Jones Griffiths, Salgado, James Nachtwey and Paolo Pellegrin… These are some of the authors I love the most. I also love some photographers who shoot in color, and I admire them for their effortlessness. However, I think that what shapes the photographer the most is practice, that’s making photography. There are many things you have to learn and manage before taking a single shot.

What direction is your photography taking?

I don’t know and I don’t ask myself, even though I realize I’m facing a change. I seldom wonder about this. I’d rather stimulate intuition.

Who do you pass the baton to and why?

To many and to no-one, I have no favorites.