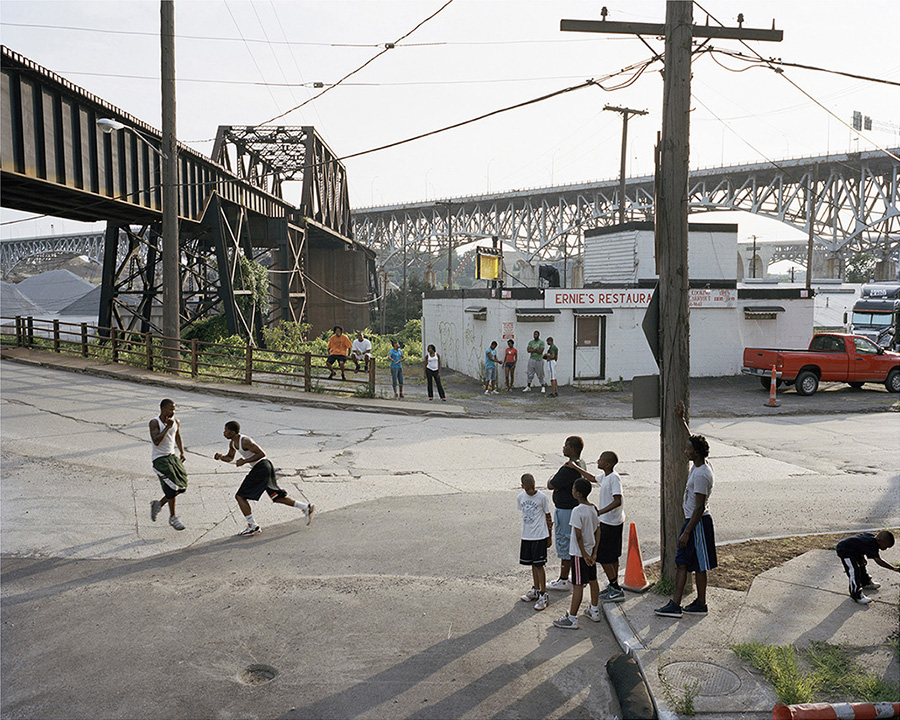

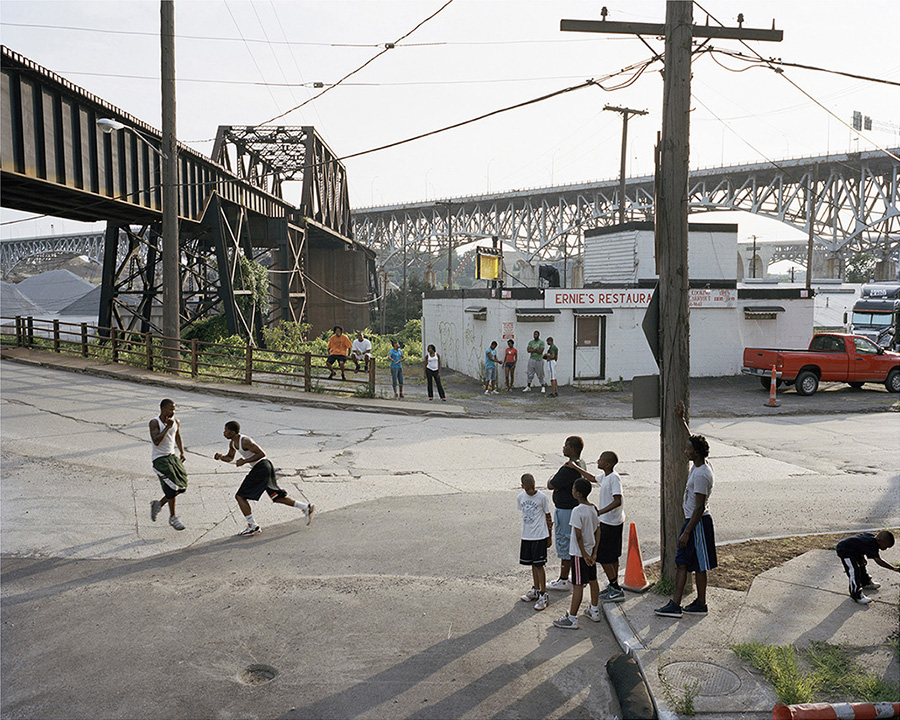

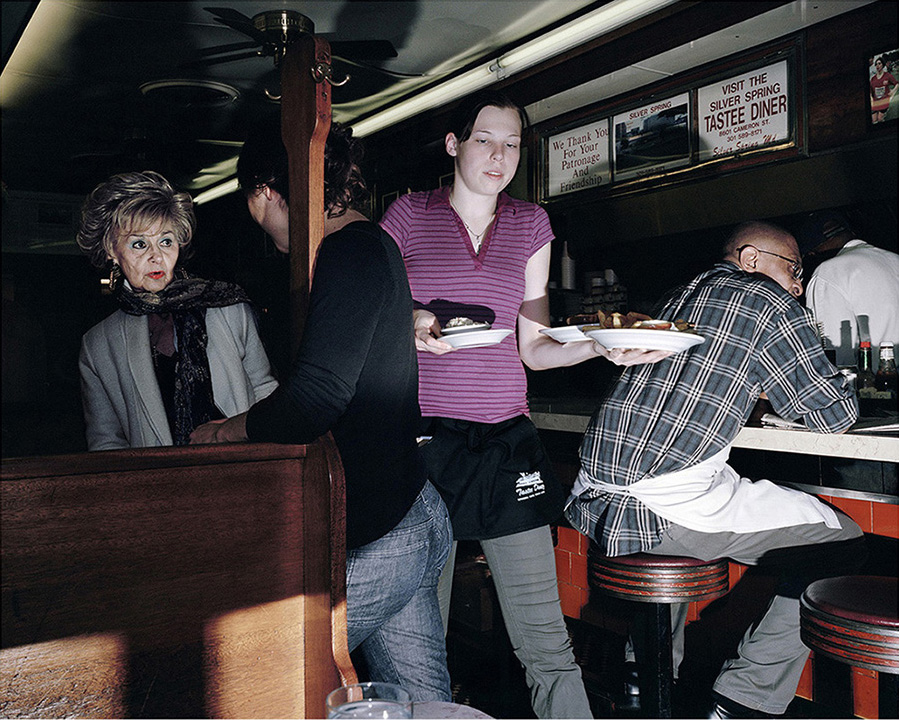

Da "The Crowded Edge"

Da "The Crowded Edge"

Da "The Crowded Edge"

Da "The Crowded Edge"

Da "The Crowded Edge"

Da "The Crowded Edge"

Da "The Crowded Edge"

Da "The Crowded Edge"

Da "The Crowded Edge"

Da "The Crowded Edge"

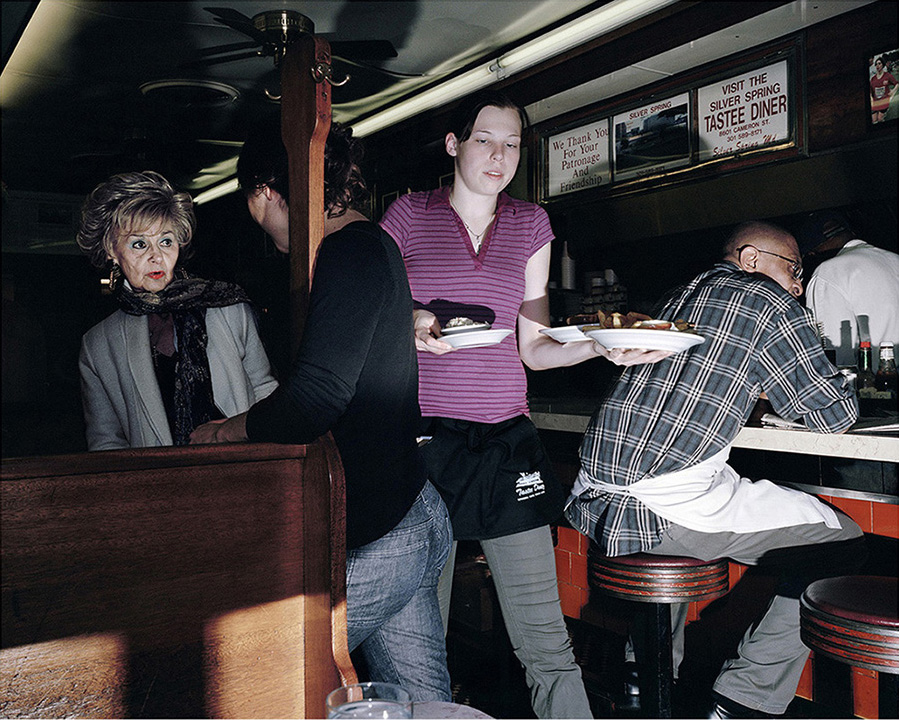

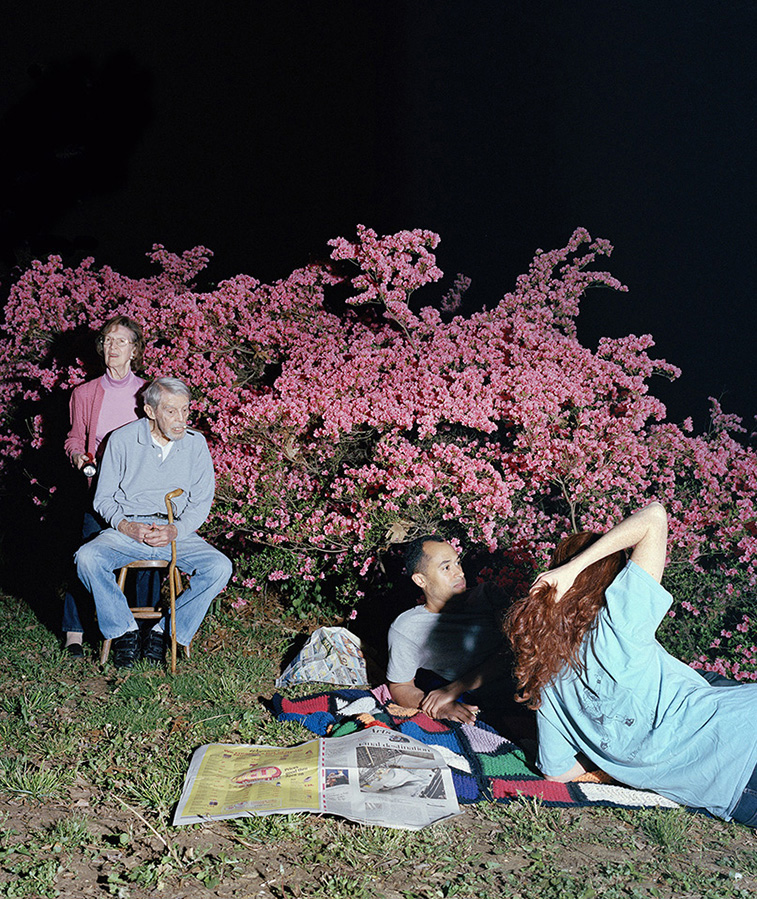

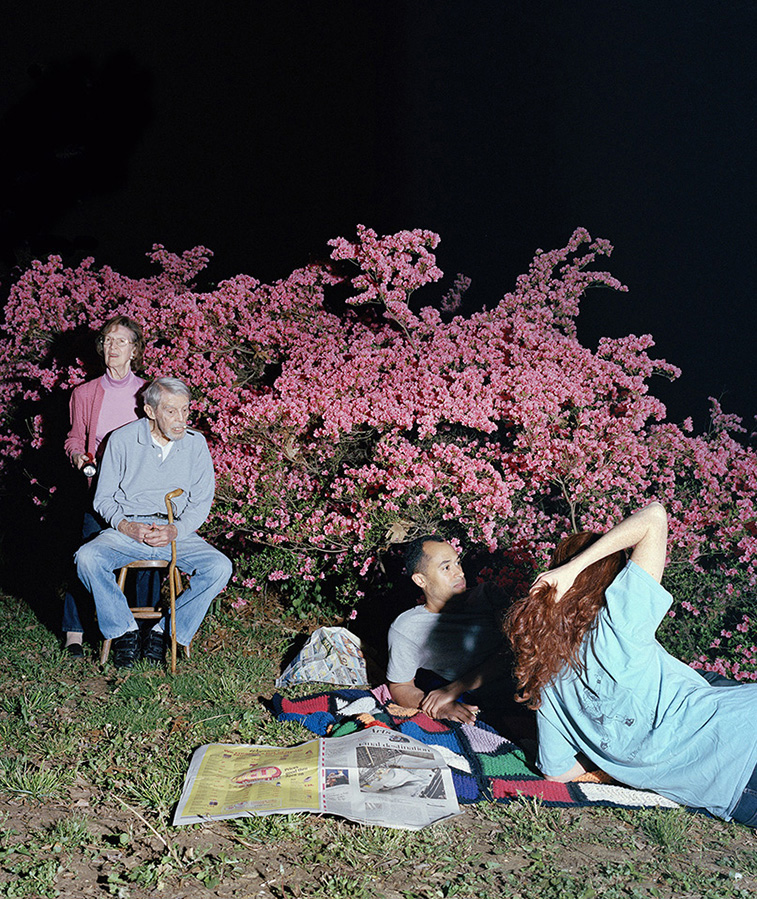

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Da "Dogwood"

Curran Hatleberg nasce nel 1982 a Washington DC e attualmente vive a Brooklyn, NY. Ha studiato all'Università del Colorado e alla Yale School of Art, e i suoi lavori più conosciuti sono esposti in imortanti gallerie nazionali e internazionali. Ai suoi progetti personali affianca l’attività di docente all’ICP di New York e al Norwalk Community College. Hatleberg ha attraversato più volte gli Stati Uniti da costa a costa per realizzare i suoi lavori fotografici, pensando i suoi viaggi come scoperta di luoghi e storie di persone. I suoi soggetti, seppur appartenenti a diverse area geografiche del paese, sono accomunati da condizioni di vita quotidiana simili.

Attraversato da una vena di critica sociale rivolta ai meccanismi - talvolta devastanti – del neoliberismo americano, il lavoro di Hatleberg ne esplora le conseguenze sulla vita della working class, mettendo in rilievo gli aspetti intimi che definiscono e consolidano le relazioni tra le persone.

Ci interessa sapere come hai iniziato i due lavori che sono presenti sul tuo sito, “The Crowded Edge” e “Dogwood”: da dove nascono sul piano personale?

Credo che la fotografia sia in parte una risposta al mondo fisico e in parte un’autoanalisi, uno strumento per filtrare il mondo esterno attraverso quello interiore. Detto ciò, ogni progetto comincia sempre nello stesso modo: mettendosi in auto e guidando a zonzo, osservando il mondo finché qualcosa cattura la mia attenzione e fa sì che il mio cervello si focalizzi. A questo punto, non resta che uscire dall’auto. Immergersi nello scenario. Gironzolare finché non succede qualcosa. Tutte le mie fotografie traggono origine dalla curiosità, da un desiderio di sentire le cose ed esprimerne la meraviglia.

Questi due lavori sono legati a commesse, borse di studio oppure sono parte di una tua ricerca personale?

Entrambi i progetti sono in fieri e li affronto come un mio esercizio artistico.

Che sbocchi hanno avuto sino ad ora? Editoria, mostre, libri... ?

Alcune immagini sono apparse in varie mostre e pubblicazioni. Più recentemente [sono state pubblicate] su Mossless negli Stati Uniti e [esposte nella galleria] Know More Games di Brooklyn, NY. Ho anche un libro di foto nuovissime in uscita l’anno prossimo.

Ci interessa molto sapere come costruisci il tuo lavoro con le persone, come le avvicini e costruisci delle relazioni, in quanto ci sembra un elemento centrale del tuo lavoro fotografico. Puoi parlarcene?

Ogni relazione comincia perché una persona mi affascina. Certe persone lanciano dei chiari segnali verso il mio radar, per un motivo o per l’altro. Magari il viso di uno sconosciuto mi ricorda quello di qualcun altro del quale, però, non ho memoria. Magari sono inusuali e soli. Magari sono seduti in un campo e stanno discutendo col cielo. Dipende. Solitamente questo magnetismo si manifesta spontaneamente e con la sensazione che ci possa essere qualche piccolo mistero da svelare - qualcosa da scuotere e portare alla luce. A quel punto, non c’è più alcun segreto. Basta dire “Ciao” e vedere che cosa accadrà.

Che tipo di reazioni hai avuto dalle persone?

La maggior parte delle volte in cui mi introduco alla gente con la fotografia, la mia curiosità è accolta con gentilezza e una leggera confusione sul perché sono interessato a loro. Non è nemmeno inusuale, al primo approccio, una reazione del tipo “Che cosa stai facendo qui?”, “Che cosa stai fotografando?”. Le cose si sviluppano da brevi conversazioni. Il tempo che trascorro con le persone, del resto, varia terribilmente. A volte mi viene offerto un pasto con la famiglia o un posto dove dormire per terra per settimane, mentre altre volte mi viene detto di sparire. Dipende da caso a caso.

Nelle tue fotografie ci sembra ci sia un’attenzione particolare alle relazioni tra le persone e tra le persone e il luogo. Il luogo in particolare, è quasi sempre presente sebbene non riconoscibile dal punto di vista geografico. È così?

Io mi impegno a descrivere uno scenario o uno sfondo prettamente americani, ma altresì a non rivelarne il luogo preciso. Mi piace che la gente si ponga queste domande sulla precisa collocazione - per farla continuare a indovinare - e lascio che sia la loro immaginazione a decidere quale luogo e quale oggetto sta osservando. Fornire la location geografica spesso non fa che rinforzare una percezione distorta o uno stereotipo che frena, parzialmente, l’interpretazione creativa. Quando tutto viene ridotto ad un mero fatto, il mistero muore e la fotografia vira verso il giornalismo. La meraviglia si sgonfia. Rimuovi queste risposte, e il mondo creato dalla fotografia si approfondirà e aprirà all’interpretazione.

Sempre in riferimento ai due lavori citati, pur se le foto sono state realizzate in luoghi diversi, potrebbero appartenere ad uno stesso luogo. È una scelta che è stata presente sin dall’inizio o è maturata mano a mano?

Questa è la mia versione dell'America. Le immagini hanno in comune un luogo dell'immaginazione, più che geografico. Mi piacciono quei posti che puoi attraversare per un motivo o per un altro, ma l'importante è che essi abbiano in sè un'innegabile "spirito Americano", indifferentemente che l'immagine sia scattata a Memphis o in Oregon.

All’inizio, il titolo di tutte le mie foto era legato alla location. È un qualcosa che fanno tutti i miei eroi: Eggleston, Friedlander, Evans, etc. Volevo rompere questo modello al fine di reintrodurre un po’ di mitologia sulla natura "espansionista" del Paese - e la sua vasta gamma di possibilità.

Nelle tue fotografie non c’è l’America dei grandi centri urbani. Come mai?

Molte delle immagini sono scattate nei grandi quartieri poveri americani, mentre il centro è molto meno presente. Sono più interessato agli spazi marginali. Ai miei occhi, sono queste le aree che mettono in luce gli incontri più sorprendenti e imprevedibili. Questi luoghi sembrano dei palchi vuoti o delle tele bianche, in quanto non presentano alcuna destinazione d’uso specifica - sono luoghi non residenziali, né commerciali o ludici. Sono terra di nessuno - zone anonime dove i confini vengono infranti.

Le tue fotografie ci sembrano esprimere domande più che risposte, e aprono a ulteriori curiosità su quei mondi. Sembra che tu stia fotografando un’America in bilico tra l'appartenenza sociale e diverse forme di degrado, anche se al contempo il tuo sguardo è sfumato e sfugge alla semplificazione. Ci puoi dire qualcosa in proposito?

Non è compito mio fornire risposte alle immagini. Preferisco creare confusione. L’ambiguità è tra le più grandi qualità della fotografia. Il mio lavoro consiste nel creare un mondo dove l’osservatore possa entrare e gironzolare, un luogo sufficientemente complicato da mantenere viva la fascinazione e ricco quanto basta per far scoprire cose sempre nuove man mano che lo si osserva.

In molte tue fotografie c’è una costante presenza di elementi che si sovrappongono, si accatastano, cose abbandonate che sono però presenti nella vita delle persone. Ci sembra che al di là della descrizione di una realtà, questo acquisti un senso più generale. Sei d’accordo?

Noi tutti viviamo attorniati da relitti, ma solitamente ci asteniamo dal notarli. Sacchetti di plastica gonfiati dal vento per strada e buche qua e là. Automobili arrugginite che riempiono i marciapiedi e i vicoli. Mulini abbandonati che riempiono il paesaggio. Certamente questi segnali sono meno presenti nei sobborghi e nelle aree di affluenza, ma sono i detriti della nostra vita quotidiana. Noi viviamo circondati da essi, e sono onnipresenti in ogni città americana. Le persone forniscono parte della narrazione, ma lo sfondo - in maniera tipicamente americana - regala quest’altra parte dell'originaria grandeur, di speranza infranta, di destino frantumato, del persistere della bellezza nonostante la nostra sofferenza - o a causa di essa. Io utilizzo queste strutture e questo scenario per aggiungere profondità narrativa. Il soggetto ha bisogno dello sfondo, e viceversa.

Inoltre, mi piace riempire visivamente l'inquadratura, attraverso una grande profondità di campo - e riempirla davvero in densità, tenerla zeppa e stratificata in modo che l’occhio dello spettatore non possa riposare. Mi piace il fatto che ogni oggetto o persona nell’inquadratura possano competere ad armi pari per conquistare l’attenzione dell’osservatore, ed essere presentati con lo stesso peso.

Nella tua fotografia c’è un’intenzione politica, una volontà di indicare una lettura politica della realtà? O è un lavoro che nasce da una volontà di scoperta, nel senso di esplorare, la realtà che vivi?

Ciò che ricerco sono quei momenti di sbalordimento che mi restano dentro, anche molto tempo dopo che si sono esauriti. La vita è davvero autentica quando viene circoscritta a questi segmenti intensi. Hai presente quella sensazione di quando hai a che fare con una cosa in modo così pieno che ogni pensiero nella tua testa svanisce e qualcosa di nuovo si affretta ad entrarvici? Si viene sopraffatti dall’emozione, ma non si è in grado di dare un nome a quel sentimento. È questo che cerco di introdurre in una fotografia.

Sicuramente c’è un’attenzione alle sfumature psicologiche delle persone che fotografi. È così anche nelle intenzioni?

Mi piace combinare le emozioni contrastanti che una persona è in grado di mostrare, tutte insieme, nello stesso momento. La maggior parte di ciò che viviamo è una specie di non-conoscenza emozionale - ciò che percepiamo è indefinito. I nostri sentimenti sono sempre stratificati e, raramente, si presentano come mono-dimensionali. Io cerco di ritrarre queste emozioni simultanee - il guazzabuglio di molteplici sensazioni che si manifestano, insieme, nello stesso momento.

Se pensiamo alla fotografia documentaria americana, che in parte rivediamo nelle tue fotografie, ti senti di appartenere a una tradizione fotografica specifica o persegui una tua linea personale? Ci sembra interessante avere il tuo punto di vista.

Sicuramente mi identifico, per lo più, nella tradizione fotografica americana - da Walker Evans a William Eggleston. Loro sono i miei eroi, ma indubbiamente questa è un’epoca diversa. Credo sia essenziale attingere dalla tradizione senza ritenersi imprigionati in essa o nell’epoca di un determinato fotografo.

Una delle differenze più evidenti, alla quale penso spesso, tra quella generazione di fotografi e la mia è che quando loro si mettevano in marcia sembravano essere meno vincolati. Forse è soltanto un mito che ho creato, ma pensateci: non esistevano social media o telefoni cellulari. Non erano costantemente connessi con la routine e con i propri cari che si trovavano lontano. Loro andavano via, in giro per il mondo, nel vento. Ovviamente esistevano ottime mappe, ma adesso il GPS guida ogni nostra mossa con la massima precisione. Adesso puoi andare nel miglior ristorante thailandese nel raggio di tre città ogniqualvolta lo desideri. È un mondo diverso, che la tecnologia ha uniformato in nome del massimo grado di efficienza.

Come affronti tecnicamente il tuo lavoro e con quali formati lavori? Cosa ti porti dietro nei tuoi viaggi?

Il mio setup per scattare è quello analogico. Uso un kit di strumenti quanto più scarno possibile. Una macchina fotografica - una Mamiya 7 - e una lente. Tengo, inoltre, un flash manuale in mano. Il treppiedi lo uso raramente, ma ne porto uno in macchina per qualsiasi evenienza. Il mio output, invece, è digitale - dalla scansione alla stampa.

La scelta di un formato piuttosto che un altro a cosa risponde? E quanto è importante o meno per te la scelta della tecnologia?

Non mi curo eccessivamente dell’attrezzatura. Qualsiasi sia il modo in cui un artista arrivi alla migliore delle sue espressioni, quello è il sistema migliore. Per me è poco importante il “come” viene realizzato qualcosa, rispetto al “cosa” rappresenta in sé. Io uso la macchina fotografica semplicemente perché la conosco bene. Abbiamo fatto molto insieme. È comoda e fluida nelle mie mani: le do un ordine e, il più delle volte, lei lo esegue. Risponde come se fosse una parte di me. Ho scelto il medio formato perchè da all'immagine tutta l'accuratezza che serve, che comunque necessita di attenzione, ma senza il grande ingombro di un banco ottico.

Sono anche totalmente dedicato alla pellicola. Principalmente perchè non mi interessa rivedere subito ciò che ho appena scattato — non voglio che una piccola rappresentazione digitale [lo schermo, ndr] influenzi le mie scelte o mi distragga da quell'attimo che ho davanti. Voglio scattare mentre le cose accadono, senza interferenze.

Quali sono gli elementi che definiscono il tuo approccio fotografico? Ad esempio: il tuo lavoro è costruito e controllato secondo un progetto definito oppure nasce nel suo evolversi, dall’incertezza dell’incontro con le persone e le situazioni?

Non sento mai l’avvicinarsi di un progetto finché non è stato avviato. Quando comincio è come se stessi guardando qualcosa che manca e non sono sicuro di che cosa sia. È come se stessi sull’orlo di qualcosa di importante che continua a sfuggirmi. Ogni progetto segue un percorso intuitivo. Raramente guardo il rullino che ho scattato prima che siano passati mesi, così che possa operare con il piglio del momento e l’istinto. In seguito, dopo aver visionato i negativi, inizio a connettere i punti e ricavarne un significato. È così che le cose vengono sviluppate.

Quanto conta la dimensione narrativa nel tuo lavoro? E come pensi le tue fotografie, come foto singole o come foto in serie/sequenza?

Lotto affinché le mie fotografie siano entrambe le cose. Da un alto, spero che ogni foto sia abbastanza forte da reggersi autonomamente. Dall’altro, nel contempo, sono profondamente interessato nel saliscendi narrativo che può realizzarsi nelle sequenze, quando le immagini costituiscono frammenti di una storia più ampia.

Senti influenze anche da altre forme espressive - il cinema, ad esempio, o l’arte?

Sì. Sono un avido lettore. Sono devoto alla letteratura. Potrei sfogliare pagine per giorni interi. Inoltre, mi sento profondamente attratto dal cinema, ancorché sia meno ferrato in materia. Queste sono le massime forme d’arte che ho in mente perché spesso si occupano della vita quotidiana - e danno un senso al caos della mia vita.

Non abbiamo trovato traccia di tuoi lavori multimediali. È una scelta? E cosa ne pensi dello sviluppo di questo tipo di media?

L'unica cosa che posso dire è che [il multimediale] mi interessa, e trovo che sia eccitante nella sua potenzialità. Magari un giorno [mi cimenterò], ma, per il momento, rimango fedele all'immagine fissa.

Come è iniziato il tuo lavoro di fotografo? E in questo momento a quali ambiti è rivolto?

Il mio inizio nel campo della fotografia non è stato dettato da ambizione, amore o impegno. Semplicemente, era qualcosa che mi piaceva e rendeva felice. All'epoca avevo studiato pittura all’università e tutte le fotografie che scattavo venivano utilizzate come spunto per i miei dipinti. Erano snapshot di amici, principalmente. Mi ci volle del tempo per capire che non ero tagliato per la pittura. Non mi piaceva il lavoro in studio o impiegare così tanto tempo per la produzione di un’immagine. Mi sentivo come se il lavoro - e spesso la mia stessa mente - fossero molto più avanti rispetto al dipinto, molto prima che questo fosse stato completato. La fotografia permetteva al mio desiderio di muoversi e vagare, abbandonare lo studio e andare a spasso alla ricerca di qualcosa di inatteso e fresco, nuovo. Ero già "on the road" per piacere, ma ad un certo punto, dopo il college, a ciò ho unito la fotografia. In seguito, sono diventato più rigoroso e ho riposto tutte le mie energie in essa. Da allora, non mi sono mai fermato.

A chi passi il testimone?

A Matt Booth.

Intervista a cura di Marco Benna

ENGLISH VERSION

Curran Hatleberg was born in 1982 in Washington DC and currently resides in Brooklyn, NY. He studied at Colorado University and at the Yale School of Art. His most renowned works are exhibited in various galleries both nationally and internationally. His personal projects are pulled alongside with his teaching at ICP, New York and Norwalk Community College. Hatleberg has embarked on numerous coast-to-coast trips around the US to compose his photographic works, deeming his travels as a discovery of new places and stories. Although belonging to different geographic areas of the country, his subjects share the same daily life conditions.

Through a social critique against the - sometimes devastating - mechanisms of the American neoliberalism, Hatleberg’s work explores its impact on the life of the working class, by highlighting the intimate aspects that define and consolidate interpersonal relationships.

We’d like to know how you started the two works featured on your website, “The Crowded Edge” and “Dogwood”. What personal perspective do they originate from?

I think photography is partly a response to the physical world and partly self-examination, a way of filtering the outside world through the inside one. That being said, every project always begins the same way: by getting in a car and just driving around, letting the world roll by until something grabs my attention and snaps my brain into focus. Then all there is to do is to get out of the car. Slide into the scenery. Poke around until something happens. All my pictures originate from a curiosity, a desire to feel things out and express that wonder.

Are these works connected to some assignment/scholarship or are they part of your personal research?

Both of the projects are works in progress and are undertaken as my artistic practice.

Where have they landed so far? The publishing industry, exhibitions, books… ?

A handful of images have appeared in a variety of exhibitions and publications. Most recently in Mossless in America and at Know More Games gallery in Brooklyn, NY. I also have a book of brand new images set for release next year.

We’re particularly keen to know how you build up your work with people, the way you approach them and create a relationship with them, because it seems to us that it’s a focal element of your photographic work. Could you tell us about it?

Every relationship starts because a person fascinates me. Someone sends sharp signals to my radar for one reason or another. Maybe a stranger’s face reminds me of someone else I know but can’t remember. Maybe they are unusual and alone. Maybe they are sitting in a field arguing with the sky. It just depends. Usually this magnetism happens naturally and with a sense that there could be some small mystery to uncover—something to shake out and bring to light. Then, there’s no secret to it. You just say hello and see what happens.

What kind of feedback have you received from people?

Most often approaching someone to photograph, my own curiosity in them is met in kind, accompanied by a mild confusion about why I am interested in them. It’s not uncommon to be approached first either, with, “What are you doing out here?” “What are you taking pictures of?” Things develop from small conversation. The duration of time-shared with someone has wild variances. Sometimes I’m offered a meal at the family table or a floor to sleep on for a few weeks, other times I’m told to beat it. Case by case, just depends.

We think that your photographs highlight a peculiar attention to both interpersonal and people-location relationships. Namely, location features in almost all images, even though it’s not recognizable from a geographic perspective. Is it so?

I’m committed to describing a distinctly American setting or backdrop, but also to withholding the precise location. I like to force those questions of specific location on the viewer—to keep them guessing—letting their imagination decide where and what they are looking at. Providing the geographic location often only reinforces a misguided preconception or stereotype that closes down part of the creative interpretation. When everything is reduced to fact, the mystery dies and the picture wanders towards journalism. The wonder deflates. Remove those answers and the world created by the photograph deepens and opens up to interpretation.

With regard to the above-mentioned works, could the respective photographs belong to the same place even though they were shot in different locations? Did you make this choice from the very beginning or did it mature progressively?

This is my version of America. The pictures share an imaginative locale rather than geographic. I like places that have been passed by for one reason or another, but what’s important is that they cast an undeniable American feeling, not whether a picture is made in Memphis or Oregon.

At first my pictures were all titled based on location. This is something all my heroes do: Eggleston, Friedlander, Evans, etc. I wanted to try disrupt that pattern, in order to reintroduce some mythology about the expansive nature of the country—its vast range of possibility.

In your photographs there’s no reference to the big urban areas of America. How come?

Many of the images are made in large, inner-city America, but downtown centers are less present. I am more interested in liminal spaces. To me these are the areas that showcase the most surprising and unpredictable encounters. These places feel like empty stages or blank canvases because they are not intended for any specific purpose—it’s a place that isn’t residential, commercial or recreational. They belong to a no man’s land, anonymous zones where boundaries break down.

It seems to us that your photographs unveil questions rather than providing answers. They induce further curiosity towards those worlds, especially because it feels as though you’re shooting America on the edge between social identity and several types of decay - yet your view remains faded and escapes simplification. Could you tell us something about this?

It’s not my role to provide answers to the pictures. Instead I want to create puzzles. Ambiguity is one of photography’s greatest qualities. My job is to create a world for the viewer to enter into and walk around in that is complicated enough to sustain prolonged fascination and rich enough to discover new things the longer one stares.

Plenty of your photos feature a constant overlaying and stacking of elements - abandoned things that are still present in people’s lives. We think this characteristic acquires a more general meaning, beyond describing reality as it is. Do you agree?

We live around abandoned things but habitually relieve ourselves of noticing them. Plastic bags skid and bump down the street on the wind. Rusting cars congest driveways and alleys. Abandoned mills clog the landscape. Sure, these signs are less present in suburbs and areas of affluence, but these things are the detritus of quotidian life, we live surrounded by them, they are ubiquitous to every American city. People provide part of the narrative, but then the backdrop supplies this other part—which is so American—of former greatness, hope gone awry, manifest destiny blown to shreds, the permanence of beauty despite our suffering, or because of it. I use structures and setting to add a narrative depth. The subject needs the backdrop and vice versa.

In addition I like to stack the frame visually, with deep focus. Really pack it densely. Keep it busy and layered so the viewer’s eye can’t rest. I enjoy when each object or person in the frame can equally vie for a viewer’s attention—can be presented with equal weight.

Does your photography comprise a political intent, some sort of intention to convey a political interpretation of reality? Or is it a work originating from your thirst for discovering as in exploring, the reality you live in?

What I am looking for are the moments of awe I stay inside long after they are over. Life rings true when it’s narrowed down to intense segments. You know that feeling when you experience something so fully, that every thought in your head disappears and something new rushes in? It’s being overcome with emotion but not being able to give that feeling a name. That’s the instant I try to jam into a picture.

Undoubtedly there’s a focus on the psychological undertones of the people you shoot. Is that so in your intentions, too?

I like the combining the contradictory emotions a person can display all at once. Most of what we experience is a kind of emotional not knowing, what we feel and is unclear. Our feelings are always layered and rarely one-sided. I try to depict those concurrent emotions—the jumble of multiple feelings running together all at once.

Thinking of the American documentary photography that we partly see in your pictures, do you feel like you belong to some specific photographic tradition or do you pursue your own personal path? It’d be interesting to know your take on this.

I certainly identify most with an American tradition of photography—from Walker Evans to William Eggleston. They are my heroes, but it’s undoubtedly a different time. I think it’s essential to take from tradition without being bound to it—to author one’s own time.

One glaring difference I often think about between that generation of photographers and my own is that when they hit the road they were seemingly less tethered. Maybe this is just mythology I have created, but think about it: there was no social media or cell phones. They weren’t constantly connecting with the life and loved ones they cherished elsewhere. They were gone. Out there in the world. Caught up in the breeze. Sure there were good maps back then but now GPS will guide every move with total precision. Now you can yelp the best Thai restaurant in a tri-city area when the mood strikes you. It’s a different world that technology has streamlined for optimum efficiency.

From a technical perspective, how do you approach your works and in which formats do you shoot? What do you bring with you when you travel?

My shooting setup is analog. I strip my toolkit down pretty bare. One camera, the Mamiya 7, with one lens. I also keep a manual flash on hand. I use a tripod very rarely but have one buried in the car in case it’s needed. My output is digital—scan to inkjet.

What informs the choice of a given format over another? How important - or not important - is the choice of technology for you?

I don’t fuss much about gear. However an artist can arrive at the best expression of their art is the best system. It matters little to me how something was made, in face of the made thing itself. I use that camera simply because I know it well. We’ve done a lot together. It’s comfortable and fluid in my hand, I give an order and most of the time it follows. I don’t have to think or do guesswork with the dials. It responds like it’s part of me. I chose medium format because I wanted the description that film size affords but still needed to remain reactive, without burdensome setup of the view camera.

I also feel devoted to film. Principally because I am not interested in seeing what I just shot right away—I don’t want that tiny digital representation dictating my choices or distracting me from the moment at hand. I want to shoot while the moment is happening without interference.

What are the defining elements of your photographic approach? For instance: is your project built and monitored according to a defined plan or does it flow as it develops from the uncertainty with people and situations?

I never feel a project coming until it’s already underway. When I begin it’s as if I am looking for something that’s missing and I’m not sure what it is. It’s as if I am on the verge of something important that keeps eluding me. Every project follows an intuitive route. I rarely see the film I’ve been shooting until months after, so I can operate on whim and instinct. Then once I do get around to looking over the negatives I start to connect the dots and draw meaning. Things push forward from there.

How relevant is the narrative dimension in your work? How do you envision your pictures - as single shots or rather as a sequence of shots?

I strive for the pictures to be both. On one hand I hope each picture is strong enough to support itself autonomously. At the same time I am deeply interested in the rise and fall narrative can take in a sequence, when pictures act as fragments of a larger story.

Do you feel any influences from other expressive forms such as the film industry or art?

Yes. I am an avid reader. I am devoted to literature. I can turn the pages of a book all day. I also feel deeply connected to film, although I am less studied in it. These are the supreme art forms in my mind because they often engage with the everyday—they make sense of the mess of life.

We have found no trace of any multimedia projects of yours. Is it a specific choice? What do you think of the development of this type of media?

All I can say is it interests me. It’s exciting in its possibility. Someday perhaps. For now, I feel loyal to the still image.

How did you start your job as photographer? What directions is it taking at the moment?

My start in photography began without ambition or love or commitment. It was just something I enjoyed happily. At the time I had been studying painting as an undergrad and all the photographs I took were used as source material for the paintings. They were snapshots of friends mostly. It took me some time to figure out I wasn’t cut out for painting. I didn’t like the studio or time commitment attached to the production of one image. It felt like work and often my mind was far ahead of the painting before it was anywhere near completion. Photography enabled my desire to move—to roam—to ditch the studio and get around to seeing something unexpected and fresh. I was already hitting the road by for fun but sometime after college I attached photography to it. Then I became more serious and put all my energy into it. I haven’t stopped since.

Who do you pass the baton to?

To Matt Booth.