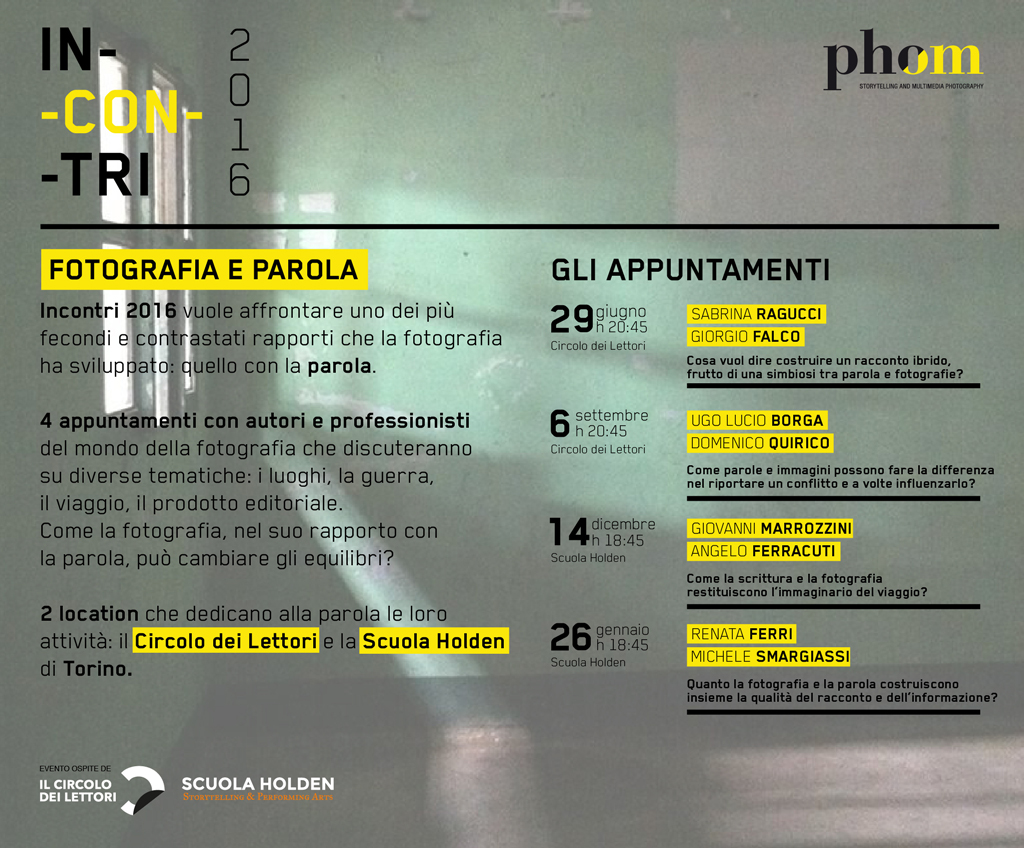

Per il secondo anno consecutivo torna “Incontri”, la rassegna di conferenze in cui Phom si confronta con fotografi ed esperti di fama internazionale, e con il proprio pubblico, sui temi che riguardano la fotografia.

Dopo il successo dei quattro appuntamenti del 2015, “Incontri” torna in due luoghi simbolo della città di Torino: il Circolo dei Lettori e la Scuola Holden, per esplorare e discutere di un tema delicato e affascinante: il rapporto tra fotografia e parola.

Quattro appuntamenti per provare a capire come immagini e parole abbiano saputo raccontare i luoghi, la guerra, il viaggio, e di come si intersechino e convivano nella costruzione di un prodotto editoriale.

Lo faremo insieme a fotografi, giornalisti, photoeditor e scrittori che hanno indagato e praticato questo rapporto.

29 GIUGNO

Circolo dei Lettori, Via Giambattista Bogino, 9 - 20,45

Sabrina Ragucci | fotografa e critica della fotografia

Giorgio Falco | scrittore

Ci parleranno del loro ultimo lavoro insieme, “Condominio Oltremare”, un incrocio di storie e immagini in una riviera romagnola desolata e fuori stagione. Ci racconteranno cosa voglia dire costruire un racconto ibrido, frutto di una simbiosi tra parola e fotografie.

6 SETTEMBRE

Circolo dei Lettori, Via Giambattista Bogino, 9 - 20,45

Ugo Lucio Borga | fotogiornalista e reporter

Domenico Quirico | giornalista de La Stampa

Per affrontare il racconto di quello che forse di più satura la nostra informazione quotidiana: i conflitti e le guerre. Come parole e immagini possano fare la differenza nel riportare un conflitto, e a volte addirittura influenzarlo?

14 DICEMBRE

Scuola Holden, Piazza Borgo Dora, 49 - 18,45

Giovanni Marrozzini | fotografo indipendente

Angelo Ferracuti | scrittore

Il viaggio, la fotografia e la parola si intrecciano in un racconto corale di esperienze condivise fra i due linguaggi.

26 GENNAIO 2017

Scuola Holden, Piazza Borgo Dora, 49 - 18,45

Michele Smargiassi | giornalista di Repubblica e autore del blog fotografico Fotocrazia

Renata Ferri | photoeditor per Io Donna e Amica - RCS Mediagroup

L'evoluzione del rapporto tra fotografia e parola: quanto questa relazione diviene fondamentale a seconda dei contesti di realizzazione e di utilizzo.

Tutti gli appuntamenti di Incontri 2016 sono ad ingresso gratuito, previa prenotazione su Eventbrite.

Per info: scrivete a info@phom.it!

Concept, struttura e contenuti, conduzione dell'incontro a cura di Marco Benna

ENGLISH VERSION

“Incontri” is back for its second year of conferences in which Phom creates discussions between photographers, internationally renowned experts and their audience on various topics regarding photography.

After the success of 2015’s conferences, “Incontri” will be held in two of the most beloved venues within Turin’s cultural scape: Circolo dei Lettori and Scuola Holden, which will host talks that will explore the delicate and fascinating relationship between photography and the written word.

There will be four encounters in which we’ll try to understand how images and words have been able to narrate wars, places, travels, and how they coexist in the creation of an editorial product.

Among our guests there will be photographers, journalists, photo editors and writers who have explored and practiced this kind of relationship.

29th of June

Circolo dei Lettori, Via Giambattista Bogino 9 - 8,45 pm

Sabrina Ragucci | photographer and photography critic

Giorgio Falco | writer

Together they will talk about their last collective work “Condominio Oltremare”, a crossroad of stories and images that take place in a desolated Italian well known riviera, during the cold seasons.

The authors will tell us about how to build a hybrid account, originated by the symbiosis between photography and words.

6th of September

Circolo dei Lettori, Via Giambattista Bogino 9 - 8,45 pm

Ugo Lucio Borga | photojournalist

Domenico Quirico | journalist at La Stampa

In this conference Ugo Borga and Domenico Quirico will talk about how to deal with two of the topics that largely fill our daily news: wars and conflicts. How can images and words make a difference in reporting war news and how can they possibly influence them?

14th of December

Scuola Holden, Piazza Borgo Dora 49 - 6,45 pm

Giovanni Marrozzini | Independent photographer

Angelo Ferracuti | writer

Travel, photography and the written word embrace in a choral account of shared experiences between the two languages.

26th of January

Scuola Holden, Piazza Borgo Dora 49 - 6,45 pm

Michele Smargiassi | journalist at Repubblica and founder of the photography blog Fotocrazia

Renata Ferri | photoeditor at Io Donna and Amica - RCS Mediagroup

The evolution of the relationship between photography and words: how it becomes fundamental according to the realisation and usage contexts.

All Incontri conferences are free, but please do reserve a place on Eventbrite.

For any kind of information write us at info@phom.it!

All conferences and curated and presented by Marco Benna.